Jump to:

Expanding claims on ocean resources

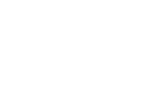

While human have relied on the ocean for millennia, the scale and diversity of today’s ocean use is considered unprecedented. Apart from fishing, there are several industries (both long-standing and emerging) that are active on the ocean. Shipping and offshore oil and gas represent the two largest sectors economically and have the most significant ecological footprint on the marine environment outside of fishing. Among sectors with a smaller but still notable footprint, marine aquaculture has grown rapidly over the last two decades. Several other industries—including marine renewables, deep-sea mining, and biotechnology—are on the horizon. In recent decades, there has been a sharp uptick in human activities on the ocean and extraction of its resources, with a clear acceleration at the onset of the 21st century.1

Global Trends in Ocean-Based Industries

Global trends by sector and percent increase since 2000. Source: Jouffray J-B, Blasiak R, Nyström M, Österblom H, Tokunaga K, Wabnitz CCC, Norström AV (2021) Blue Acceleration: an ocean of risks and opportunities. Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA) Report.

Many ocean-based industries are growing faster than the global economy itself. According to the OECD, ocean industries generated USD 1.5 trillion in economic activity in 2010; this amount is expected to double to USD 3 trillion in 2030.2 Some sources refer to the trendline of human expansion into the ocean as the “blue acceleration.” As diverse and sometimes competing user groups seek to access food, material, and space in the ocean, there are calls to carefully consider concerns around equity and sustainability.3 While international dialogues and policy programs have advanced rhetoric of a “blue economy” in recent years, there is a lack of clarity on what the blue economy entails (e.g., whether there is a prerequisite for sustainability) and who benefits from such activity.4

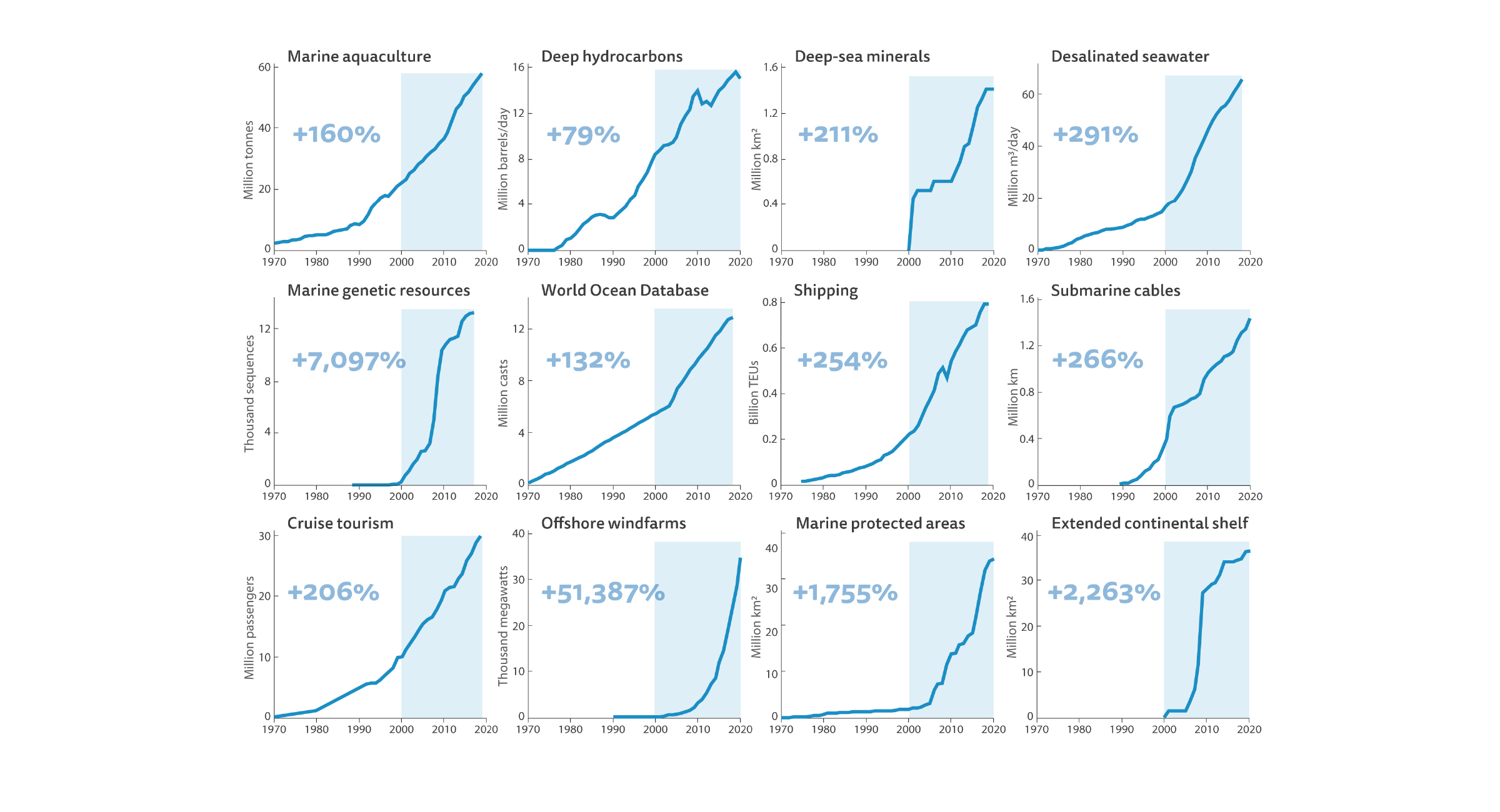

Claims on Ocean Resources for Food, Material, and Space

The authors of the source paper identified and categorized these claims through an iterative process that sought to understand ocean uses of direct relevance for ecosystem sustainability, human well-being, and economic growth. Source: Jouffray, J.-B., R. Blasiak, A.V. Norström, H. Österblom and M. Nyström. 2020. “The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion Into the Ocean.” One Earth 2 (1): 43–54.

Footprint of individual industries

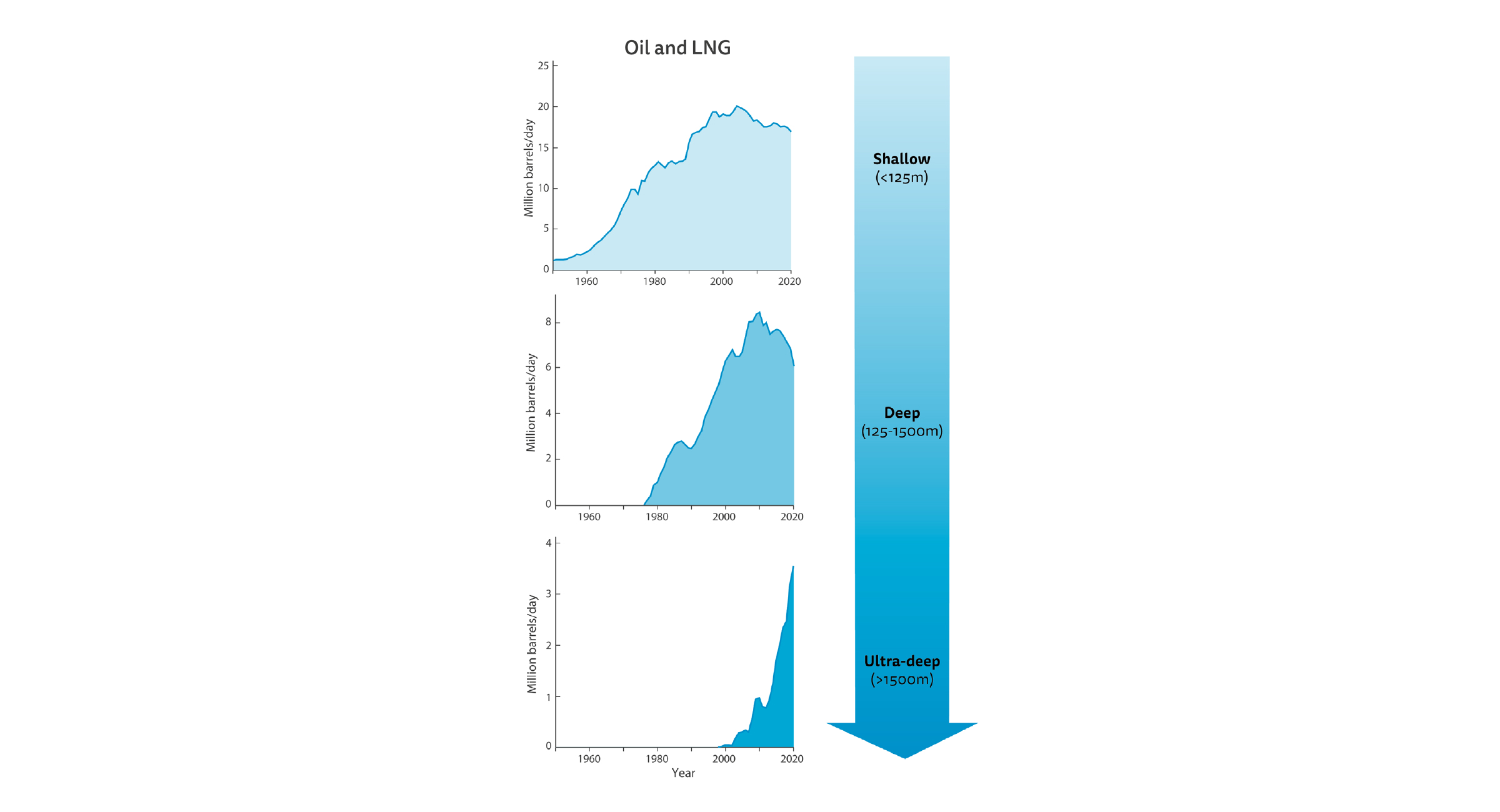

The environmental footprint of ocean-based activities varies by industry. Offshore extraction, which represents roughly 30 percent of global oil and gas production, is rapidly increasing.5

From noise pollution to spills to habitat damage, offshore oil and gas production has a wide-ranging and pervasive impact on marine habitat and wildlife. During 2000-2020, an estimated 70 percent of the major discoveries of conventional hydrocarbon deposits were discovered offshore; further reserves are expected to exist in the deep sea. By value, the oil and gas sector is the largest ocean-based industry, accounting for one-third of the total value of the ocean economy.6

Current trends suggest that offshore oil and gas production is slated to increasingly venture into deepwater and ultra-deepwater sectors, as many fields in shallow waters are nearly exhausted.7 As compared to newly discovered onshore fields, recently discovered offshore fields are about 10 times larger, which has provided an economic incentive for industry, in spite of high upfront costs and inherent environmental risk. Four countries—Brazil, the United States, Angola, and Norway—account for the majority of global deepwater and ultra-deepwater oil production.8 Since 2005, each of these four countries has increased its share of offshore oil production from deepwater or ultra-deepwater sources; this proportion is highest in Brazil and the United States, which represent about 90 percent of global ultra-deepwater production.9

Production trends over time of crude oil and LNG

Temporal trends in global offshore production volumes of crude oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) from 1950-2020, across water depth categories: shallow (< 125m), deepwater (125-1500m), and ultra-deepwater (>1500 m). Data from Rystad Energy. Source: Jouffray J-B, Blasiak R, Nyström M, Österblom H, Tokunaga K, Wabnitz CCC, Norström AV (2021) Blue Acceleration: an ocean of risks and opportunities. Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA) Report.

As the offshore sector increasingly expands into deep and ultra-deep waters of the ocean, studies tracking the implications of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010 provide insight on the potential risks to ecological and human communities. The Deepwater Horizon spill led to an uncontrolled release of 5 million barrels of oil in the Gulf of Mexico, resulting in immediate death of marine life and substantial financial losses for tourism and fishing industries. However, a recent study found that biodiversity of microbes was flattened at sites closest to the spill, suggesting that the oil may have long-lasting impacts on the ecosystem for years after the initial spill, given that microbes make up the base of the food chain.10

The volume of global maritime traffic continues to grow, with direct and indirect ramifications for the marine environment. The global maritime industry has steadily increased in both the number of ships and in total shipping capacity. Roughly 80 percent of maritime traffic occurs in the Northern Hemisphere, with nine of the ten busiest ports all in Asia. Although considered less carbon-intensive than other land- or air-based transport options, shipping is responsible for approximately 3.1 percent of global greenhouse emissions (as well as “black carbon”), which are expected to increase 50-250 percent from 2012 levels by 2050.11 Shipping also contributes to pollution, invasive species, habitat destruction, and marine mammal mortality through dumped and spilled oil and waste, ballast water discharges, ship strikes, noise pollution, and dredging for shipping channels.

While most forms of aquaculture production involve relatively benign practices, environmental impacts do occur in the form of invasive species, disease, unnatural competition with wild fish, conversion of coastal habitat (mangroves), impacts on the seafloor, additional pressures on wild fisheries (for fish meal and fish oil) and chemical and antibiotic use. These impacts vary by species, geography, production system, and intensity. As the aquaculture industry is projected to expand to meet growing global food demands, advocates have called for the incorporation of sustainability concerns into the industry’s growth agenda.

Among emerging industries, the ocean is threatened from a variety of extractive or polluting industries such as deep-sea mining, desalinization, marine renewables, sand mining, submarine cables, and dredging and dumping. Both governance institutions and the conservation community are racing to understand the extent and impact of these emerging industries, which are venturing into increasingly remote areas of the ocean.

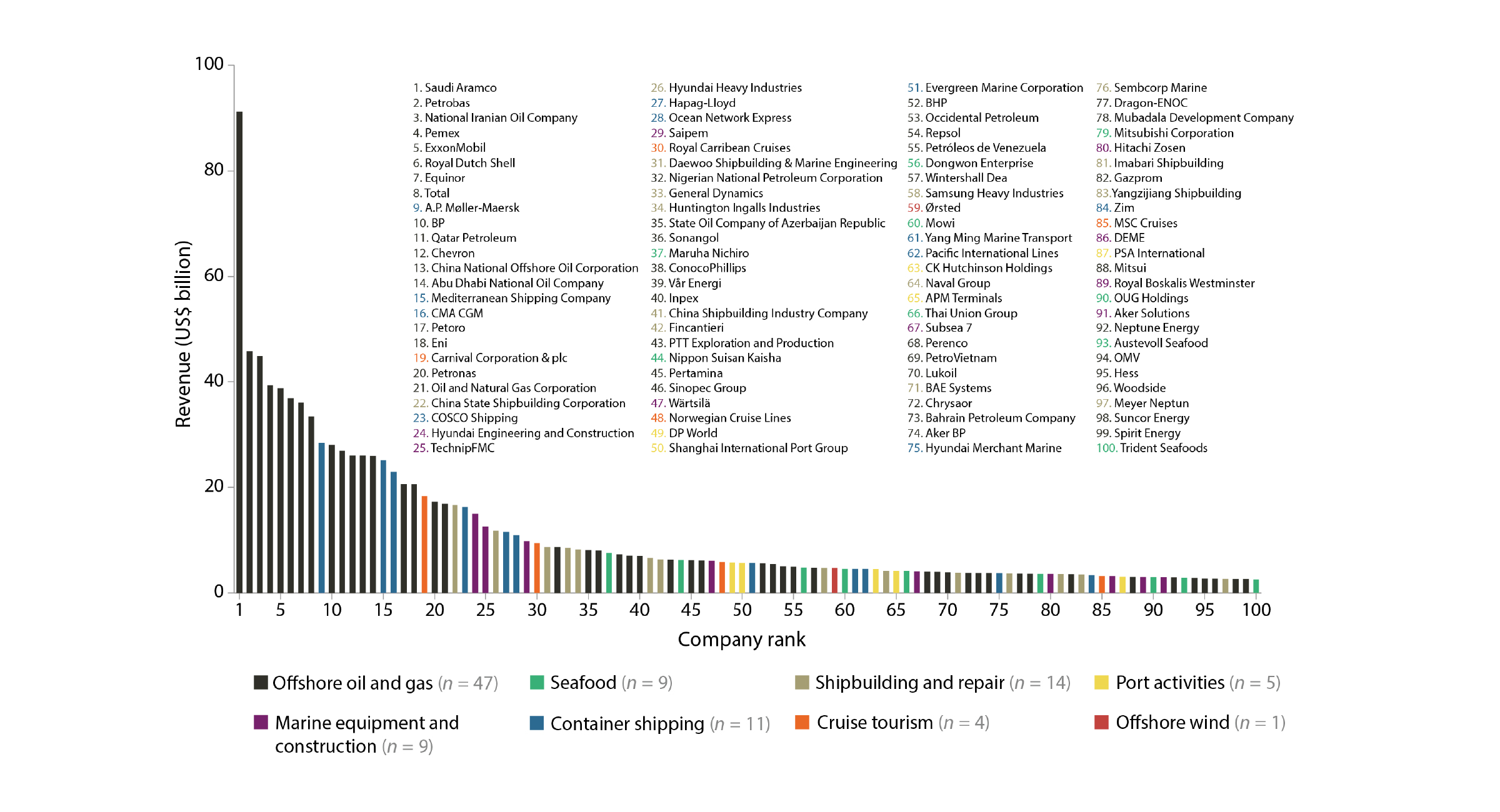

Ocean industries by revenue

A recent study found that revenues generated by the ocean economy are concentrated in a handful of companies. This analysis found that among ocean economy industries, the 100 largest companies (the “Ocean 100”) generated 60 percent of total revenues (based on 2018 values).12 Among the top 10 largest industries, nine are based in the oil and gas sector. Understanding this level of concentration in the ocean economy provides both risks and opportunities for integrating sustainable and equitable uses of the ocean.

Top 100 transnational corporations linked to the ocean economy

The Ocean 100: The hundred largest transnational corporations in the eight core industries of the ocean economy by annual review (based on 2018 figures). Only revenues that could be explicitly linked to the ocean economy were included. Source: Virdin, J. et al. “The Ocean 100: Transnational corporations in the ocean economy.” Sci. Adv. 7, 1–11 (2021).

Equity considerations of the Blue Acceleration

These changes are occurring against the backdrop of an already dynamic and evolving context in the marine environment, as climate change is altering species migrations, opening up new areas for potential shipping routes and mineral extraction, forcing considerations around ocean-based climate measures, such as the placement of offshore wind turbines. Given that economic benefits from the “blue acceleration” have historically flowed to dominant states and corporations—and harm has disproportionately impacted developing nations and local communities—there are calls to more explicitly center equity concerns to support a just and sustainable ocean economy.13

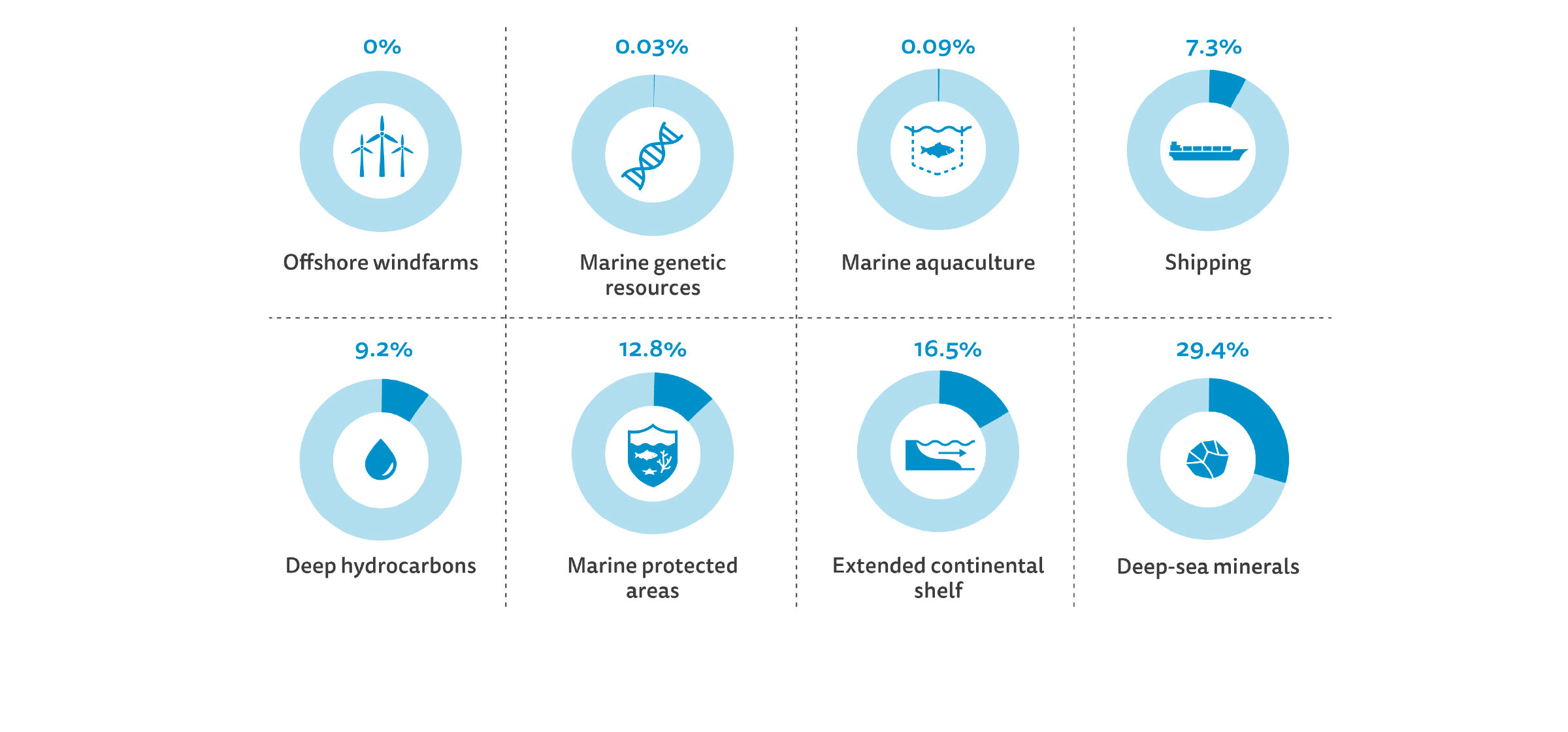

The impact of the blue acceleration is particularly relevant for small island development states (SIDS) and coastal least developed countries (LDCs), which are often heavily reliant on the ocean for their economy and livelihoods, while simultaneously bearing disproportionate burden of climate change.14 Many observers and practitioners point to a continued need to consider the question of “who benefits in the blue acceleration?” and to advocate for equitable inclusion, knowledge sharing, and profit sharing with SIDS and LDCs as it relates to ocean economies.

Contributions of SIDS and LDCs to the Blue Acceleration (% of global)

The relative contributions of SIDS and LDCs to the Blue Acceleration. Note that some of these trends can be strongly driven by just a few countries. For instance, Angola is responsible for 78% of offshore deep hydrocarbon production from SIDS and LDCs, while Singapore accounts for more than 65% of container port traffic in SIDS and LDCs. Source: Jouffray J-B, Blasiak R, Nyström M, Österblom H, Tokunaga K, Wabnitz CCC, Norström AV (2021) Blue Acceleration: an ocean of risks and opportunities. Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA) Report.

Notes

- Jouffray, J.-B., R. Blasiak, A.V. Norström, H. Österblom and M. Nyström. 2020. “The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion Into the Ocean.” One Earth 2 (1): 43–54.

- OECD. “The Ocean Economy in 2030.” OECD Publishing, Paris, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264251724-en.

- Jouffray, J.-B., R. Blasiak, A.V. Norström, H. Österblom and M. Nyström. 2020. “The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion Into the Ocean.” One Earth 2 (1): 43–54.

- Ibid.

- Jouffray J-B, Blasiak R, Nyström M, Österblom H, Tokunaga K, Wabnitz CCC, Norström AV (2021) Blue Acceleration: an ocean of risks and opportunities. Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA) Report.

- Ibid.

- International Energy Agency. “Offshore Energy Outlook” IEA: Paris, France. 2018.

- EIA. “Offshore oil production in deepwater and ultra-deepwater is increasing.” EIA. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=28552.

- Ibid.

- Hamdan, L.J. et al. “The impact of the Deepwater Horizon blowout on historic shipwreck-associated sediment microbiomes in the northern Gulf of Mexico.” Scientific Reports 8 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27350-z.

- Michelin, M., et al. 2020. “Opportunities for Ocean-Climate Action in the United States.” Report. San Francisco, CA: CEA Consulting.

- Virdin, J. et al. “The Ocean 100: Transnational corporations in the ocean economy.” Sci. Adv. 7, 1–11 (2021).

- Jouffray J-B, Blasiak R, Nyström M, Österblom H, Tokunaga K, Wabnitz CCC, Norström AV (2021) Blue Acceleration: an ocean of risks and opportunities. Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA) Report.

- Ibid.