Over the past two decades, Brian O’Donnell has been a leader in wildlife and land conservation. Now, as director of the Campaign for Nature, supported by the Wyss Foundation, he has the ambitious task of securing protection for 30 percent of the world’s land and ocean by 2030 (known as 30×30). For Brian, an important next step is ensuring that when world leaders come together for the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, postponed from earlier this year and now set to take place in Kunming, China, in May 2021, they bring the commitments needed to adopt this science-driven framework.

Our Shared Seas sat down with Brian to learn more about this effort, and what it means for our ocean. In this interview, he shares tangible actions that the marine conservation community can take to help secure an ambitious global deal for ocean protection in 2021.

Whale Shark feeding in the waters off Isla Mujeres, Mexico

What do you see as the role of marine philanthropy in supporting the 30×30 vision?

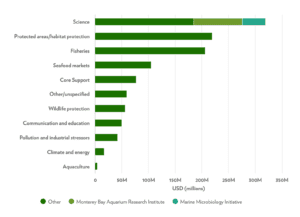

Explore how funding for habitat protection stacks up against other ocean issues. Link to the Funding Primer.

Philanthropy can and should play a role in the 30×30 effort. Globally, philanthropy has a much lower focus on the environment compared to other issue areas. In the United States, about three percent of philanthropic dollars go towards a general category under the environment, which also includes things like animal welfare protection. We need a huge investment into areas of high biodiversity, especially areas in lower-income countries.

We are grateful to our current marine philanthropy partners, but we need them to be advocates within the philanthropic community and within governments to push for more money and engage their peers in this effort. They’re all heroes, but it is it is too small of a community right now. We need more funders to join in, given what’s at stake.

What are the strengths of current efforts and where should philanthropy do more to support the designation and ongoing management of marine protected areas?

In many ways, philanthropy has a similar bias that we have as advocates: we all like the gratitude of immediate accomplishments. There’s a kind of excitement about a new designation, or a new protected area. This is where a lot of the advocacy work goes, and that’s where a lot of the philanthropic money goes. It’s gratifying and feels tangible.

There’s a huge need in our community to start putting as much effort into campaigning for finance as we do for designations. We tend to think we need campaigns for designations and then the financing will flow, but it doesn’t work that way. We need campaigns for finance in countries that are designating MPAs. We need campaigns in large donor countries. And we need campaigns to bring more philanthropy dollars to the table.

There’s a huge need in our community to start putting as much effort into campaigning for finance as we do for designations. We tend to think we need campaigns for designations and then the financing will flow, but it doesn’t work that way.

What should be on the action list for the marine conservation community to increase the chances of securing the 30×30 target and achieving an ambitious deal in Kunming next year?

The “blocker” nations haven’t fully shown their cards yet, but as we get into the height of the negotiations, some nations will start to show their opposition. There will likely be a dozen or so countries that are going to have a problem with 30×30. We need efforts in each of those countries to help show grassroots support for 30×30. One opportunity is to provide funding and other support to develop that kind of civil society engagement and to demonstrate the economic benefits for countries to engage in 30×30.

We also need a parallel campaign on finance in conjunction with our work on policy. At the Campaign for Nature, we’re realizing just how big of a job that is. It will require nearly the same effort as securing the 30×30 deals in policy. We can unlock quite a few resources from domestic governments, official development assistance, and the private sector, but it’s going to take an organized campaign effort. This is a place where philanthropy can invest a limited amount of money and have huge returns in terms of the amount of money that comes back into MPA designations and management over the long run.

Related article: A Primer on Climate Change and Marine Biodiversity Photo: Jayne Jenkins / Coral Reef Image Bank

On the science front, we need to make a stronger climate case for MPAs so that we can unlock some of that climate finance and elevate this in the political agenda. We also need to use science to show how leader or blocker countries can show pride in their protected areas. Instead of seeing the target as a challenge, we need to use the science to engage with civil society and build political momentum to show how a country can be incredibly proud of its biodiversity.

On the philanthropy side, funders must recognize that the time for safe bets is over. We need to take some risks in the near term. Traditionally, the funding community has been very cautious and, in many cases, only willing to work on sure bets and in places with a strong rule of law. Given the urgency of this crisis, we need funding for places that are harder to reach and where others haven’t engaged. We must empower, fund, and trust local communities to show leadership. This will require philanthropy to get out of its usual comfort zone, but it’s critical to the long-term success of marine conservation.

We can unlock quite a few resources from domestic governments, official development assistance, and the private sector, but it’s going to take an organized campaign effort. This is a place where philanthropy can invest a limited amount of money and have huge returns in terms of the amount of money that comes back into MPA designations and management over the long run.

Protecting 30 percent of the planet’s ocean and land will require significant investment. A recent independent report commissioned by your team found that this level of protection would require an average annual investment of about USD 140 billion by 2030. Currently, the world invests roughly USD 24 billion in marine and terrestrial protected areas. What is your vision on how we will close the gap to secure necessary financing for protected areas?

In some ways, this is the hard medicine for many to swallow. For the past few decades, we have been hoping for a way to fully “unlock the private sector” to prompt this massive influx of private capital into ocean conservation. This hasn’t panned out at scale.

If we want to unlock major private money into ocean conservation, we need governments to set up major new frameworks, incentives, and regulations. There is money from the private sector that can support ocean conservation, but we need political will to make that happen. Good examples are cruise taxes or tourism fees, but we need to make sure that governments are willing to put those in place—and then we need to make sure that money stays within the MPAs.

Today, most of the money for MPAs comes from domestic budgets. This must increase if we are to expand the size of MPAs and achieve 30×30. We recognize governments of developing countries that are already facing extreme poverty can’t afford that, especially while the world is in the midst of a pandemic. These countries will do what they can, but wealthier nations of the world must markedly increase their official development assistance (ODA) to help this happen. There’s a big role for debt for nature coming forward.

A key way to unlock this funding is through BIOFIN, which is a UN agency that supports countries in implementing finance solutions to reach their national biodiversity targets. In the past, countries have developed their plans for how they’re going to meet targets for biodiversity, but they haven’t developed financial plans for accomplishing this.

Studies have shown that staff capacity shortfalls are limiting the potential of many MPAs around the world from achieving their objectives. In addition to the campaign for finance that you propose, do we also need a campaign for investing in staff capacity to successfully manage MPAs?

Absolutely, this is critical. We tend to reinvent this over and over again with each new MPA, rather than learn from what’s worked in other sites. First, we need to find ways to incorporate indigenous knowledge in this process. Second, we need to make sure that Indigenous people and local communities have the management responsibility for these areas, including the ownership and tenure rights they need to guarantee that success.

We can’t just think about it in terms of only co-management with governments because that doesn’t place enough trust or respect in the approaches of Indigenous people. When I think about 30×30 and how it can look, I think we need a diversity of strategies. That’s something that Dr. Tom Lovejoy, the scientist who’s worked on the Amazon for decades, always says: to protect the diversity of life, we need a diversity of strategies. That is also true for marine conservation.

The 30×30 campaign has a very clear goal that is easy to communicate, which is great. But we shouldn’t simplify things too much. It is dangerous to suggest that we must create 30 percent of exactly the same type of protected area everywhere in the ocean. That is disenfranchising for local people and will not incorporate indigenous knowledge and management into the final strategy.

When I think about 30×30 and how it can look, I think we need a diversity of strategies. That’s something that Dr. Tom Lovejoy always says: to protect the diversity of life, we need a diversity of strategies. That is also true for marine conservation.

What are concrete steps that marine NGOs and funders can take now to point governments on a more successful path to prioritize and finance biodiversity?

First, leaning in heavily on debt for nature is a key opportunity. The most vulnerable countries in the world are hurting in a big way. We should look for opportunities to help them in the near term while ensuring they have natural resources to sustain biodiversity in the long term.

Secondly, tourism is a major driver for many protected areas. The leading presumption is that after the Covid-19 lockdowns, there will be a resurgence in tourism. We need to work with developing nations so that they don’t feel like their only option is to exploit natural resources. When the world does return to some degree of tourism and travel, this investment will be critical. Investing in places now to maintain those tourism economies over the long term is essential.

Third, there is a promising opportunity to eliminate some of the silos between climate and biodiversity finance. To date, most climate finance has gone into the energy side of the equation. We are now seeing a huge interest in the nature-based side of the equation. Done right, this finance stream can provide a major influx of resources for biodiversity conservation. To get ourselves out of this climate mess, the world needs to find a way to put a price on carbon. We must make sure that nature receives some of that money in the long term, which could lead to significant new investments in biodiversity.

Finally, there have been conversations recently about a One Health approach to global health, where we’re not just looking at treatment of diseases, but are thinking about prevention. When we start to think about health from this lens, the conservation of nature is essential to prevent future pandemics. It’s certainly cheaper to invest in that now than to face another pandemic down the road.

To date, most climate finance has gone into the energy side of the equation. We are now seeing a huge interest in the nature-based side of the equation. Done right, this finance stream can provide a major influx of resources for biodiversity conservation.

Read our follow-up interview with Brian O’Donnell here to learn more about the policy state of play on the post-2020 framework negotiations process and what needs to happen between now and next year’s COP to achieve 30 percent protection for the ocean.