Photo: FAO

The role of “ocean aid” in achieving global targets for ocean conservation and sustainable use by 2030

The aim of this guest essay is to provide ocean philanthropists with a brief introduction to trends in ocean-targeted official development assistance (ODA), to demystify the latter for the former, and suggest some ways that the two might more closely work together and enhance their individual efforts. As ocean-related philanthropy increasingly moves beyond North America,1 we will need both of these sources of capital to work in lockstep as part of a global effort, if we are to achieve both ocean-related SDG targets and end poverty and hunger.

When policymakers emerge from fighting the Covid-19 pandemic, their attention will hopefully refocus on the global ocean and recapturing momentum from the “ocean super year,”2 in a sprint to 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) related to ocean use and conservation.3 To date, progress towards achieving the ocean-related SDG targets has lagged,4 even as ocean use and industries have accelerated.5 In this context, action taken in the tropical waters of lower income countries over the next decade may determine not only whether the ocean-related SDG targets are met, but also those goals for ending poverty and hunger.

To illustrate the tropical nexus between ocean conservation and global poverty reduction efforts, scholars mapped human dependence on marine ecosystems for coastal protection and income and nutrition from fisheries, suggesting over 775 million people live in coastal areas with high dependence scores, largely throughout the tropics (notably small island developing states).6 For example in fisheries, higher income countries have generally improved fisheries management over recent decades, while lower income coastal and island countries have faced a worsening situation in terms of overcapacity, fishing productivity and stock status.7 However, some 78 percent of the large-scale fishing vessels operating in the coastal waters of lower-income countries are flagged to higher income countries.8

At the same time, roughly half of the world’s 25 “coral reef states” are lower income countries – i.e., those 25 countries estimated to have jurisdiction over 85 percent in aggregate of all warm-water coral reefs.9 Similarly, the majority of the world’s estimated 137,000 square kilometers of mangrove forests are located in the tropics, as highly efficient carbon sequestration systems10 whose twentieth century decline has slowed due likely to a combination of conservation efforts and reduced forest cover.11 In sum, actions taken in the waters under the jurisdiction of lower income states throughout the tropics may well determine the success of any global push to achieve international policy targets by 2030 (e.g., ocean-related SDGs, UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration, UN Decade of Ocean Science, the emerging “30 x 30” target proposed under the Convention on Biological Diversity, etc.).

With a focus of ocean conservation, management, and restoration efforts in the tropical waters of lower income countries, discussions of funding become particularly important. Essentially, these efforts often take the form of public goods, and particularly institutional reforms, that will require scarce capital in tropical contexts. For example, fisheries management reforms often require significant government expenditures up front, even if the economic benefits outweigh the costs over time.12 Funding provided (i) by higher income governments as “official development assistance (ODA)”13 or (ii) by philanthropy will likely be critical to these efforts, though not the only options for lower income countries.14 These two fundamental sources of external funding for ocean conservation, management and restoration efforts in lower income countries – what I am referring to colloquially as “ocean aid” – still seem to work uneasily alongside each other, if at all.

Trends in World Bank ODA targeted to ocean conservation, resource management, and restoration

A group of scholars recently began study of the trends in ocean-related ODA over recent decades, but a lack of transparency in funding allocations makes this extremely challenging.15 Unpublished analysis suggests a general increase in ocean-related ODA over the last five years.16 However, given the difficulty in comprehensively synthesizing the landscape of ocean-related ODA, it is useful to look at the World Bank as an example, as one of the largest funders shaping sustainable use of coastal ecosystems and resources.17, 18

Together with the Global Environment Facility at the global level, as well as regional development banks and individual higher-income governments, the World Bank provides a large share of the fisheries-related ODA (which has long been one of the key components of ocean-related ODA).19 Some of my colleagues recently completed a review of trends in World Bank ODA to small-scale fisheries over fifty years,20 that is likely indicative of the organization’s shift in funding priorities for the ocean more broadly, and perhaps other major ODA providers.

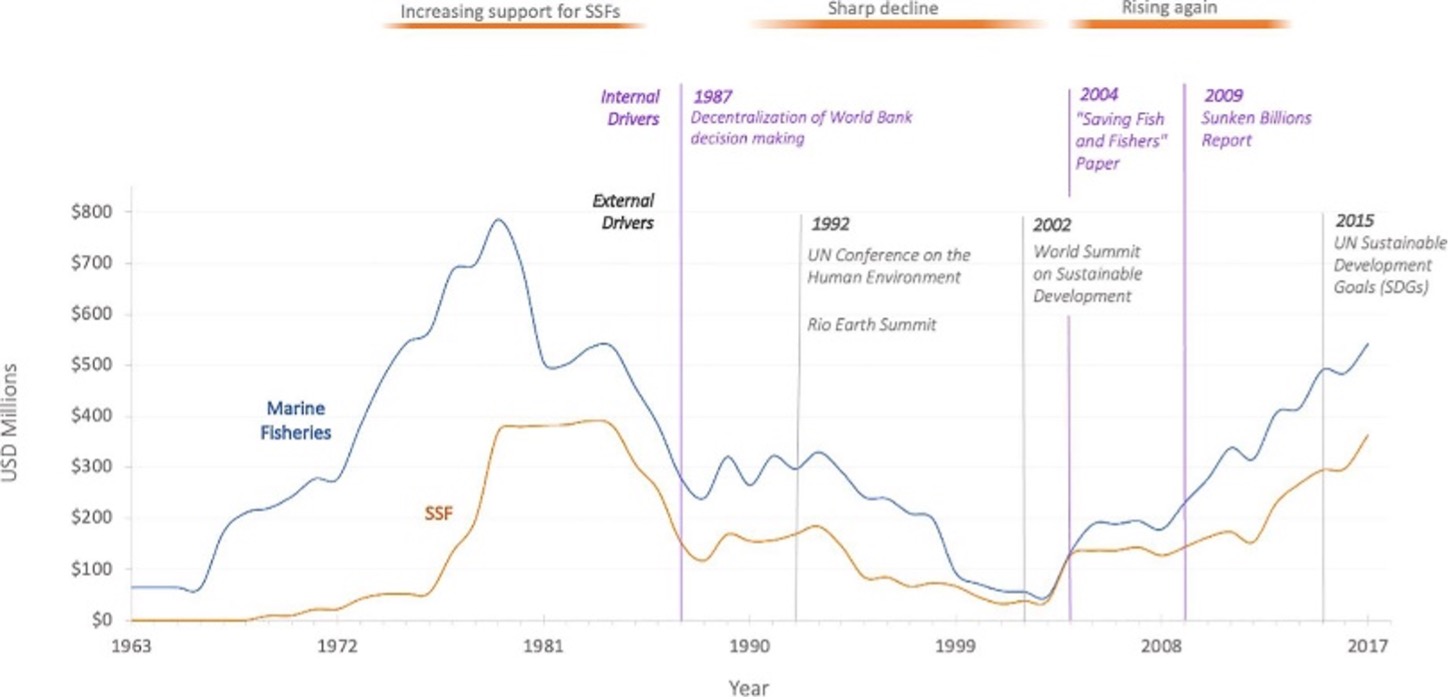

After the World Bank’s first marine fisheries project in 1963, the organization funded at least 134 projects with a marine fisheries component, for a total of over USD 2.48 billion, of which approximately 47 percent (~USD 1.17 billion) was targeted to marine small-scale fisheries.21 The World Bank’s engagement in marine fisheries appears from funding trends to have occurred in three distinct periods: rising support from the 1970s to mid-1980s; a sharp decline in funding in the mid-to-late 1980s and low levels of funding throughout the 1990s; and a steady return to funding in the mid-2000s up to the present (Figure 1).

Figure 1. World Bank funding in USD millions targeted to support marine fisheries and the subsector of small-scale fisheries over time (1963-2017) as real dollars (November 2018 dollars). Key internal (purple) and external (gray) drivers of World Bank funding targeted to support marine fisheries over time (not exhaustive). Aid amounts are represented as total active funding over time, rather than annual new allocations. Source: Hamilton et al. (2021).

As Figure 1 illustrates, the focus of World Bank funding for fisheries shifted over time from pure economic development in the early era, to governance and multi-dimensional environmental goals in the current period. This shift in focus and growth in funding over recent years was due to a number of factors, many of which were internal to the World Bank’s organization, as well external drivers on its activities, and included: (i) the changing norms around the model of investment, from a more development-centric paradigm, to a focus on poverty reduction and governance reform; (ii) the presence and influence of individual fisheries staff who pushed for investment in fisheries (or not); (iii) the development of a key partnership with the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) after the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development, providing grant funding committed for fisheries governance reform and sustainable management; (iv) changes in internal decision-making processes, towards more decentralized and demand-driven ‘project cycle’ to determine funding allocations (Figure 2); (v) changing perceptions of fisheries projects as risky and difficult to measure and evaluate, (vi) shifting emphasis from traditional growth to multi-dimensional objectives, (vii) rising interest in the fisheries sector by the governments of both donor and recipient countries, (viii) pressure from the environmental movement starting in the 1990s, and (ix) the rise of sustainable development discourses in key global meetings.22

Figure 2. The World Bank project cycle. Source: Hamilton et al. (2021)

Interestingly, despite the modern increase in World Bank funding for marine fisheries, re-focused on strengthening governance and sustainable management, total funding for both capture fisheries and aquaculture averaged only about 1.8 percent of total funding allocated to agriculture from 1968 to 2018 (although in the current era this has increased, up to 5.4 percent in 2018). Of note, the regional development banks have allocated a slightly higher average percentage of funding to capture fisheries and aquaculture over this same time period, though in many years did not fund any of these projects.23

Over the last five years, the World Bank has broadened its focus from marine fisheries, to the full range of ocean-based economic activity labelled in some cases as the “blue economy”, through the establishment of a multi-donor global trust fund – “ProBlue” – to support global analyses and project development.24 The fund serves as a vehicle for the World Bank to work with countries to carry out the studies and analysis to identify potential larger project investments in ocean conservation and resource management, and receives support (directly or through parallel funds) from the governments of a number of high income countries (Canada, Denmark, the European Commission, France, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and the United States). According to the annual report, in its first full year of operation in fiscal year 2020, the trust fund provided some USD 40 million in support of the design and delivery of 507 projects equivalent to over USD 3.6 billion. Under the umbrella of the “blue economy”, the trust fund and the World Bank’s project funding largely falls now under four themes: (i) improved fisheries governance, (ii) reduced plastic pollution, (iii) enhanced sustainability of ocean economy sectors, and (iv) integrated ocean management.25

Trends in ocean-related ODA to address key governance challenges

The World Bank’s shift over time from a focus on fisheries development to governance and resource management, among other goals, and now more recently a broader ocean-wide scope around a sustainable ocean economy, is likely representative of current of future directions ocean-related ODA. I would expect that the key themes in ocean governance identified by Campbell et al. (2017)26 probably capture much of the ocean-related ODA from global and regional organizations:

- Food production, e.g. World Bank, Global Environment Facility (GEF) and some regional development banks’ support for tropical fisheries governance, and particularly for small-scale fisheries;

- Biodiversity conservation, e.g. GEF funding for marine protected areas (note that while there is a trend towards establishing increasingly large marine protected areas globally,27 I’m not sure that many are supported by ODA) as well as for biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ);

- Industrialization, e.g. World Bank and some regional development banks’ (e.g. the Inter-American Development Bank) funding focused on the sustainability of the growing ocean economy, particularly in small island developing states, though terms like the “blue economy” have been defined differently by different governments and stakeholders, and in some cases policy goals have been focused on increased ocean extraction;

- Global environmental change, e.g. the Green Climate Fund support for coastal adaptation; and

- Pollution, notably plastic pollution reduction, e.g. the World Bank programs in South Asia,28 GEF funding.

While indicative and not exhaustive, the above themes and global or regional examples likely reflects trends in bi-lateral ocean-related ODA as well. For example, the annual Our Oceans conference typically features commitments from high income governments, and the now-postponed 2020 conference focused on six “areas of action”: (i) sustainable food from the ocean, (ii) protected areas, (iii) sustainable blue economies, (iv) climate change, (v) a clean ocean, and (vi) maritime security.29 Similarly, a panel of fourteen heads of state convened in 2020 by the Government of Norway highlighted a longer list of key themes in governance for a sustainable ocean economy, and focused on a set of “transformations” that can be expected to inform ocean-related ODA in the coming years, including: (i) integrated ocean management (“sustainable ocean plans”), (ii) enhancing the sustainability of specific ocean economy sectors (“ocean wealth”); (iii) conservation of ocean biodiversity (“ocean health”), including reducing greenhouse gas emissions, protecting and restoring ecosystems, reducing pollution; (iv) ocean equity, and (iv) ocean knowledge, as part of the UN Decade of Ocean Science.30

In sum, with a shift from economic development to ocean governance over recent decades, the ocean-related ODA has reflected to some extent the growing attention to the ocean from international policymakers, e.g. with an attempted Global Partnership for Oceans in 2012, the focus on oceans at the twentieth reunion of the Earth Summit, the Economist World Ocean Summits, the Our Oceans conferences, a dedicated Sustainable Development Goal in the 2030 Agenda, discussions of a new agreement on the biodiversity in ABNJ under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Treaty, discussions at the World Trade Organization on fisheries subsidies, the recent high-level panel of heads of state on the ocean economy led by the Government of Norway, to name a few.

Box 1: 2022 and the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture

Toward the end of 2021, the Illuminating Hidden Harvests assessment will synthesize available information on small-scale fisheries, followed by the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture. These are likely to highlight the importance of ocean use to a large number of vulnerable groups and communities, as the international community assesses the uneven effects and burdens of the pandemic.

Looking ahead: pathways for cooperation between philanthropy and ODA to accelerate ocean conservation, management, and restoration in the tropics.

Given challenges of transparency,31 it is not clear that there is a consensus on the trajectory of ocean-related ODA over the last decade. What is clear is that it has become more focused on issues related to governance and ocean conservation, management, and restoration (as opposed to economic development) than in past decades. At the same time, global attention to the ocean from policymakers has increased, now with clear conservation and resource management targets for which the world is already lagging.

Attention from philanthropy to marine areas beyond North America is growing, and presents an opportunity for a more coordinated and consolidated approach to funding ocean conservation, management and restoration in the tropics – where success or failure in achieving ocean-related SDG targets will likely be determined. Essentially, as we begin to emerge from the wreckage of the pandemic in the coming years, can ODA and philanthropy work together to help accelerate ocean conservation, management and restoration in the tropics, towards achieving the 2030 agenda and targets? What are pathways for building upon the complementarity between different but mutually-supporting funding models (Box 2)?

Box 2: Ad hoc comparison of strengths and comparisons in the funding models of philanthropies and development aid agencies

| Philanthropies | Development aid agencies | |

| Scale of funding (per project), Size | Typically in USD millions | Typically in USD tens or hundreds of millions |

| Scale of funding (per project), Time | ~2 years | ~5 years |

| Types of expenditures | Advocacy consultation and training, research, etc. | Preference for goods, infrastructure, or government budget support |

| Types of recipients | NGOs, research agencies, etc. | Governments |

| Project cycle | Faster, compared to aid | Dependent upon government demand |

| Decision-making | Board approval | Board approval |

| Assessment of risk | Higher tolerance | Lower tolerance |

| Access to other resources | Network of leading research institutions | Dialogues with governments |

For such collaboration to happen and pool scarce global resources to support ocean conservation, management, and restoration in the tropics, each of these two different types of institutions must invest time to understand each other. Each is unique – for instance, World Bank funding is largely (if not almost solely) provided to governments that determine whether or not a project occurs. Considering the strengths and weaknesses of these different types of institutions, a range of different scenarios could be envisaged for greater collaboration, from higher to lower impact, but lower to higher feasibility. These options include:

A. Global Pooled Fund (institutional-level cooperation):

The theoretical ideal might be for the two sources of aid to combine and expand funding into one mechanism that could support ocean public goods in the tropics, e.g. a “global ocean fund”. The closest parallel at the moment would likely be the International Waters Program of the GEF (essentially an ocean-related portion of this global fund, disbursed to tropical countries via a number of “implementing agencies” such as the World Bank, UN agencies, some large non-governmental organizations, etc.), and to a lesser extent the ProBlue fund at the World Bank (a fund of a number of higher income countries, disbursed via the World Bank). The new Global Fund for Coral Reefs that is currently fundraising for a target of USD 125 million in grants may also provide an example.32

The allure of a global fund or pooled ODA and philanthropic funds would be to leverage complementary features of each to both increase efficiency of efforts and to leverage additional funds. For example, World Bank funding decisions are decentralized and driven by recipient governments, via the planning process shown in Figure 2. However, without a fund like ProBlue, fewer resources are available to carry out the analyses and dialogue to support inclusion of ocean-related projects in that planning process. In that scenario, a fund with support from philanthropy could serve as a seed fund that leverages a much larger ODA portfolio.

However, the current global funding mechanisms (including GEF and World Bank ProBlue fund) are governed under relatively complex rules that may make participation by philanthropies difficult if not impossible in practice – leaving this large and growing pool of funds on the sidelines (not to mention the concentrated pools of capital generated from the core ocean economy industries,33 which could in theory be deployed via a mechanism such as an “ocean equity tax”34). There is likely a case to be made for a global ocean fund and the need to support ocean public goods in the tropics, but stitching together ODA and philanthropy, much less private sector, may be years away (though perhaps worth pursuing nonetheless).

B. Informal Cooperation (typically at the project-level):

In the meantime, there is a lot of productive and informal cooperation that could occur between ODA and philanthropy, at the level of individual projects rather than organizations. Project managers at ODA providers such as the World Bank can partner with philanthropies towards aligned objectives and where ODA recipients agree, without any need for formal agreements. For example, I can remember incredibly productive collaboration with NOAA in fisheries projects I managed at the World Bank, where the latter was already supporting fisheries legal reforms and surveillance patrols in Liberia, and the former provided observer training and support. No funds changed hands between NOAA and the World Bank, nor legal agreements signed, yet we worked productively together with the Government of Liberia, and in some cases traveled together and coordinated logistics.

Such collaboration can occur between ODA providers and philanthropy where project managers and program officers work together, without any formal agreement. There are many reasons why such collaboration could be mutually reinforcing: e.g., ODA providers have institutionalized dialogue with tropical governments (for example to discuss or support policy reforms, enforcement of compliance, etc.) and can leverage larger amounts of funding in some cases; while philanthropies can easily fund civil society partners (philanthropies can select grant recipients directly, whereas governments are typically the recipients of ODA), and perhaps most importantly, can fund monitoring and evaluation as well as research and learning (e.g. local universities).

All too often, ocean-related ODA does not include the type of monitoring to support impact evaluation where outcomes are causally attributed to interventions. (In my experience, governments often did not want to use scarce project funds for monitoring and evaluation costs.) In contrast, philanthropy is well suited to help ensure that this evaluation and learning takes place.

Given the above points, I would suggest the following practical considerations to enhance collaboration between ODA and philanthropy to accelerate ocean conservation, management, and restoration:

a. Institutional information exchange to facilitate project-level collaborations, even if institutionalizing a common funding mechanism is farther down the road. Essentially, in the short-term the most fruitful collaboration is likely to happen at the project level, where funding is not exchanged between philanthropies and development aid agencies, but each agrees to fund complementary activities in support of a broader plan or policy. This type of informal collaboration at the project-level will occur when the respective teams build a partnership. However, the transaction costs of identifying these teams and opportunities and building such partnerships can be high. For this reason, to the extent that a mechanism could be established to formally exchange information and facilitate such collaboration, it could reduce transaction costs and help respective staff find each other amidst large organizations.

Transparency in the size and scope of ocean-related ODA and philanthropy in the tropics can be further improved, so that both are incorporated into a common tracking system that actually links to relevant SDG targets. With shared information, there is no reason that the relevant ODA project managers and philanthropic program officers could not meet periodically to ensure that both know what the other is doing (e.g. looking together at a map of interventions, or themes), with the agreement that where opportunities for collaboration exist they will be pursued. Such exchanges could be the jumping off point for collaboration between project managers and program officers, even in existing activities.

If by good timing and luck these meetings and exchanges result in close collaboration in just a handful of geographies, the benefits would likely exceed the transaction costs. At a minimum, participating organizations could learn from each other what is working and what is not. This type of mechanism to help exchange information and facilitate project-level collaboration, even though funding is not exchanged between philanthropies and development aid agencies, might take the form of a “funders’ roundtable”, meeting on the margins of other international ocean conferences, comparing funding maps, sharing latest key research findings on priority themes, and identifying specific places or themes for a focus on project-level collaboration.

b. Eventually, institutionalize coordinated funding, into one or more pooled funding mechanisms for ocean conservation, management and restoration in the tropics. Ocean public goods in lower income countries, or ABNJ, are of global interest, given internationally-agreed goals. There is a case to be made for one or more global funding mechanisms, that could pool ODA and philanthropy (and potentially private sector contributions) to both enhance the size and efficiency of current efforts. Such mechanisms could potentially also accommodate private sector contributions from a “global ocean equity tax”,35 given the concentration of revenues in the current ocean economy,36 and likely inequality in the benefits from ocean use. [Note: The purpose of ocean equity tax, as proposed by Osterblom et al. (2020), is to “develop and implement a global ocean tax to reallocate parts of profits to places where environmental resources are harvested and where management actions, capacity-building, conservation or restoration are required.”]

In conclusion, as governments emerge unevenly from the pandemic, and even as contexts and challenges may change in ways not yet fully understood, the international goals for ocean conservation, management, and restoration remain, and the deadlines approach. The need for aid to support these efforts in the tropics will be even greater, particularly as many governments (notably small island developing states) will have more debt and fewer resources for public goods. We have used and heard “all hands on deck” statements and metaphors for years if not decades, so I’ll resist the temptation here. But nonetheless, the sprint to 2030 will require significant aid to the tropics if humanity is to achieve the ocean-related SDG targets. This guest essay has aimed to briefly summarize recent trends in ocean-related ODA for philanthropies, in the hopes that the two sectors can combine efforts much more closely during the coming decade.

Dr. John Virdin is director of the Coastal and Ocean Policy Program at the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions. Virdin worked for more than 10 years at the World Bank, most recently as acting program manager for the Global Partnership for Oceans, a coalition of more than 150 governments, companies, nongovernmental organizations, foundations, and multi-lateral agencies. He advised the Bank on ocean and fisheries governance and helped it increase its lending for sustainable oceans to more than USD 1 billion. His work led to the development of programs that provided more than USD 125 million in funding for improved fisheries management in six West African nations and some USD 40 million for fisheries and ocean conservation in a number of Pacific Island nations.

Notes

- Blasiak et al. 2019. Towards greater transparency and coherence in funding for sustainable marine fisheries and healthy oceans. Marine Policy 107: 103508

- https://oursharedseas.com/can-the-super-year-for-the-ocean-still-make-a-come-back/#:~:text=At%20the%20start%20of%20this,policy%20decisions%20impacting%20ocean%20health.

- Singh et al. 2018. A rapid assessment of co-benefits and trade-offs among Sustainable Development Goals. Marine Policy 93: 223-231

- United Nations Economic and Social Council, Special Edition: Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2019), p. 39.

- J.-B. Jouffray, R. Blasiak, A. V. Norström, H. Österblom, M. Nyström, The Blue Acceleration: The trajectory of human expansion into the ocean. One Earth 2, 43–54 (2020)

- Selig et al. 2018. Mapping global human dependence on marine ecosystems. Conservation Letters 12: e12617

- Ye, Y and N Gutierrez. 2017. Ending fishery overexploitation by expanding from local successes to globalized solutions. Nature Ecology and Evolution 1: 0179

- McCauley et al. 2018. Wealthy countries dominate industrial fishing. Science Advances 4: eaau2161

- UN Environment (2019) Analysis of Policies related to the Protection of Coral Reefs-Analysis of global and regional policy instruments and governance mechanisms related to the protection and sustainable management of coral reefs. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Pendleton et al. 2012. Estimating global “blue carbon” emissions from conversion and degradation of vegetated coastal ecosystems. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043542

- Friess et al. 2019. The state of the world’s mangrove forests: past, present and future. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 44: 89-115

- Mangin et al. 2018. Are fishery management upgrades worth the cost? PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204258

- Hynes, W and S Scott. 2013. The Evolution of Official Development Assistance: Achievements, Criticisms and a Way Forward. OECD Development Cooperation Working Papers No. 12. OECD: Paris, France.

- Wabnitz, CC and R Blasiak. 2019. The rapidly changing world of ocean finance. Marine Policy 107: 103526

- Blasiak et al. 2019. Towards greater transparency and coherence in funding for sustainable marine fisheries and healthy oceans. Marine Policy 107: 103508

- Yoshioka et al. 2020. Tracking international aid for ocean conservation and climate action. Presentation to the Virtual Conference on Blue Economy and Blue Finance: Towards Sustainable Development and Ocean Governance. Asian Development Bank Institute. See: https://www.adb.org/news/events/blue-economy-and-blue-finance

- Basurto et al. 2017. Strengthening Governance of Small-Scale Fisheries: An Initial Assessment of Theory and Practice. Report to the Oak Foundation. https://nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/content/strengthening-governance-small-scale-fisheries-initial-assessment-theory-and-practice

- Hamilton et al. 2021. How does the World Bank shape global environmental governance agendas for coasts? 50 years of small-scale fisheries aid reveals paradigm shifts over time. Global Environmental Change 68: 102246.

- Yoshioka et al. 2020. Tracking international aid for ocean conservation and climate action. Presentation to the Virtual Conference on Blue Economy and Blue Finance: Towards Sustainable Development and Ocean Governance. Asian Development Bank Institute. See: https://www.adb.org/news/events/blue-economy-and-blue-finance

- Hamilton et al. 2021. How does the World Bank shape global environmental governance agendas for coasts? 50 years of small-scale fisheries aid reveals paradigm shifts over time. Global Environmental Change 68: 102246.

- Hamilton et al. 2021. How does the World Bank shape global environmental governance agendas for coasts? 50 years of small-scale fisheries aid reveals paradigm shifts over time. Global Environmental Change 68: 102246.

- Hamilton et al. 2021. How does the World Bank shape global environmental governance agendas for coasts? 50 years of small-scale fisheries aid reveals paradigm shifts over time. Global Environmental Change 68: 102246.

- Bennett et al. 2021. Recognize fish as food in policy discourse and development funding. Ambio 50: 981-989.

- World Bank. 2020. ProBlue Annual Report 2020: Healthy Oceans – Healthy Economies – Healthy Communities. World Bank: Washington, DC.

- World Bank. 2020. ProBlue Annual Report 2020: Healthy Oceans – Healthy Economies – Healthy Communities. World Bank: Washington, DC.

- Campbell et al. 2017. Global oceans governance: new and emerging issues. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 41: 517-543.

- Gruby et al. 2020. Policy interactions in large-scale marine protected areas. Conservation Letters 14: e12753

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/sar/brief/plastic-free-rivers-and-seas-for-south-asia

- https://www.ourocean2020.pw/areas-of-action/

- https://oceanpanel.org/ocean-action/files/transformations-sustainable-ocean-economy-eng.pdf

- Blasiak et al. 2019. Towards greater transparency and coherence in funding for sustainable marine fisheries and healthy oceans. Marine Policy 107: 103508

- https://globalfundcoralreefs.org/

- Virdin et al. 2021. The ocean 100: transnational corporations in the ocean economy. Science Advances 7: eabc8041

- H. Österblom, C. C. Wabnitz, D. Tladi, Towards Ocean Equity (World Resources Institute, 2020), p. 33.

- H. Österblom, C. C. Wabnitz, D. Tladi, Towards Ocean Equity (World Resources Institute, 2020), p. 33.

- Virdin et al. 2021. The ocean 100: transnational corporations in the ocean economy. Science Advances 7: eabc8041