Advances in fisheries transparency technologies have enabled new fields of fisheries research that can provide an evidence base to help inform government policy and management of human activities at sea. Our Shared Seas spoke with Dr. Jennifer Raynor—a Member of the Board of Trustees for Global Fishing Watch and an Assistant Professor of Natural Resource Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison—about how transparency tools from Global Fishing Watch have shaped ocean research and policy, including how these tools have transformed her own professional journey.

Chinese fleets anchored in Sadong port, Ulleung-do, South Korea due to bad weather in North Korean waters. There are two types of boats shown: trawlers (30-35 m long) and lighting boats (55-60 m long with much taller structures above deck). Photograph taken on December 6, 2016. Photo: Ulleung-gun County Office

Can you share your perspective on how applied data from Global Fishing Watch has evolved over the years, especially with respect to speed and scale?

There’s no question in my mind that Global Fishing Watch has been a transformational force for ocean transparency. The organization has built the first-ever publicly available map to track the location of every industrial fishing vessel globally, in near real-time.

We can almost take for granted that this data is now available and ready to be used for research. Before Global Fishing Watch was founded in 2015, there was no feasible way to do globally-based fisheries research. Most countries are highly protective of their fisheries data, so the organization’s work in this space represents a complete leap and bound increase in what we know about human use of the ocean. Year after year, Global Fishing Watch keeps raising the bar, especially given recent advances in machine learning and satellite coverage.

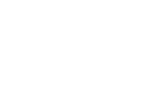

Under the new open ocean project (recently selected for investment by The Audacious Project), Global Fishing Watch will process millions of gigabytes of satellite data to reveal all industrial human activity at sea, including activities that we cannot currently see using vessel-based Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). I think this new project will be just as transformational in mapping human uses of the ocean as the organization’s original industrial fishing map.

There’s no question in my mind that Global Fishing Watch has been a transformational force for ocean transparency. The organization has built the first-ever publicly available map to track the location of every industrial fishing vessel globally, in near real-time.

Some Chinese lighting vessels photographed when avoiding typhoons at Ulleung-do, South Korea in 2016 and 2017. They typically have 400-700 light bulbs aboard. Photo: Ulleung-gun County Office

What are a few highlights that illustrate how Global Fishing Watch data has shined a light on fishing activity and helped bring about policy or behavior change on the water?

There are so many examples to point to. Global Fishing Watch has a catalogue of success stories on its site describing how it has helped turned data into action for ocean stewardship.

For me, one of the biggest success stories was the exposure of illegal fishing in North Korea. Lots of large industrial vessels were heading from China towards North Korea, despite UN sanctions that prohibit foreign vessels from fishing in these waters. There were also tragic cases of small-scale fishing boats washing up in Russia and Japan, with crews either missing or dead. The hypothesis was that these boats were coming from North Korea to fish in more remote areas, as they were unable to compete with the more technologically advanced Chinese vessels that had taken over their home fishing grounds.

Global Fishing Watch, in collaboration with partners in South Korea, Japan, Australia, and the USA, used four different satellite technologies to identify fishing vessels in the North Korean waters. They found roughly 900 Chinese fishing vessels fishing in North Korean waters in violation of the UN sanctions. This was the largest known case of IUU fishing by a single fleet. It was also one of the first cases to leverage satellite technologies to shine a light on dark fleets, meaning fleets that are intentionally hiding their behavior.

At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, fishing activity in this region fell by 50 percent. Some of this decline was likely related to the pandemic’s lockdown-related measures, but there was also a significant amount of international attention on what was happening in the region. Combined, I think these two factors really drove the decline in IUU fishing activity.

This case is important because there were real implications for human lives, food security, and livelihoods. Researchers estimate that the Chinese vessels caught more than 160,000 metric tons of Pacific flying squid during 2017-2018, worth hundreds of millions of dollars. And many North Korean fishers took life-threatening risks to fish in remote areas. Global Fishing Watch and its partners helped expose these illegal behaviors and create an unprecedented picture of fishing activity in an opaque region.

Global Fishing Watch uses satellite imagery and radar to detect industrial ocean-going vessels, including those that do not publicly broadcast their location and are considered “dark” in monitoring systems. Source: Global Fishing Watch

How do most governments perceive fisheries transparency, and has this evolved over time?

Historically, some countries might have viewed transparency as a threat to the fishing industry. Now, more countries are seeing the win-win opportunities.

The fact that many countries have partnered with Global Fishing Watch to provide their vessel location data provides evidence that this shift is underway. Norway, many Latin American and South American countries, and others have provided their vessel location data to Global Fishing Watch. This signals a sea change—there’s a growing awareness that governments can help protect their country’s fleet by understanding the scope of fishing activities.

Historically, some countries might have viewed transparency as a threat to the fishing industry. Now, more countries are seeing the win-win opportunities.

Government officials in Peru use Global Fishing Watch data to monitor industrial fishing activities in its national waters. Photo: Diego del Rio / Global Fishing Watch

Have these transparency tools ever supported monitoring and enforcement in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)?

There’s also been a lot of work to use Global Fishing Watch data to understand what’s happening in and around MPAs. One high-impact case took place near the Galapagos Marine Reserve in 2020 when the organization exposed distant water fishing for jumbo flying squid, a high-value fishery. The research found roughly 600 foreign vessels—of which about 95 percent were flagged to China—actively fishing for squid on the high seas. In fact, Chinese vessels accounted for nearly 99 percent of the fishing near the Galapagos.

The Galapagos is one of the most biodiverse places in the world, and the satellite data found that the distant water fleet was fishing on the edge and within the MPA. Global Fishing Watch published data on its website and shared reports with the governments of Ecuador, Peru, and Chile to help hold China accountable. The case received a lot of international attention, including in The New York Times and elsewhere. After all of this attention starting in 2021, the Chinese fleet stayed away from the Galapagos for the first time in 5 years.

This shows that shining a light can change behavior without any one country necessarily spending a lot of money on enforcement– there’s high value in a deterrence effect when people know that fishing activity is being monitored.

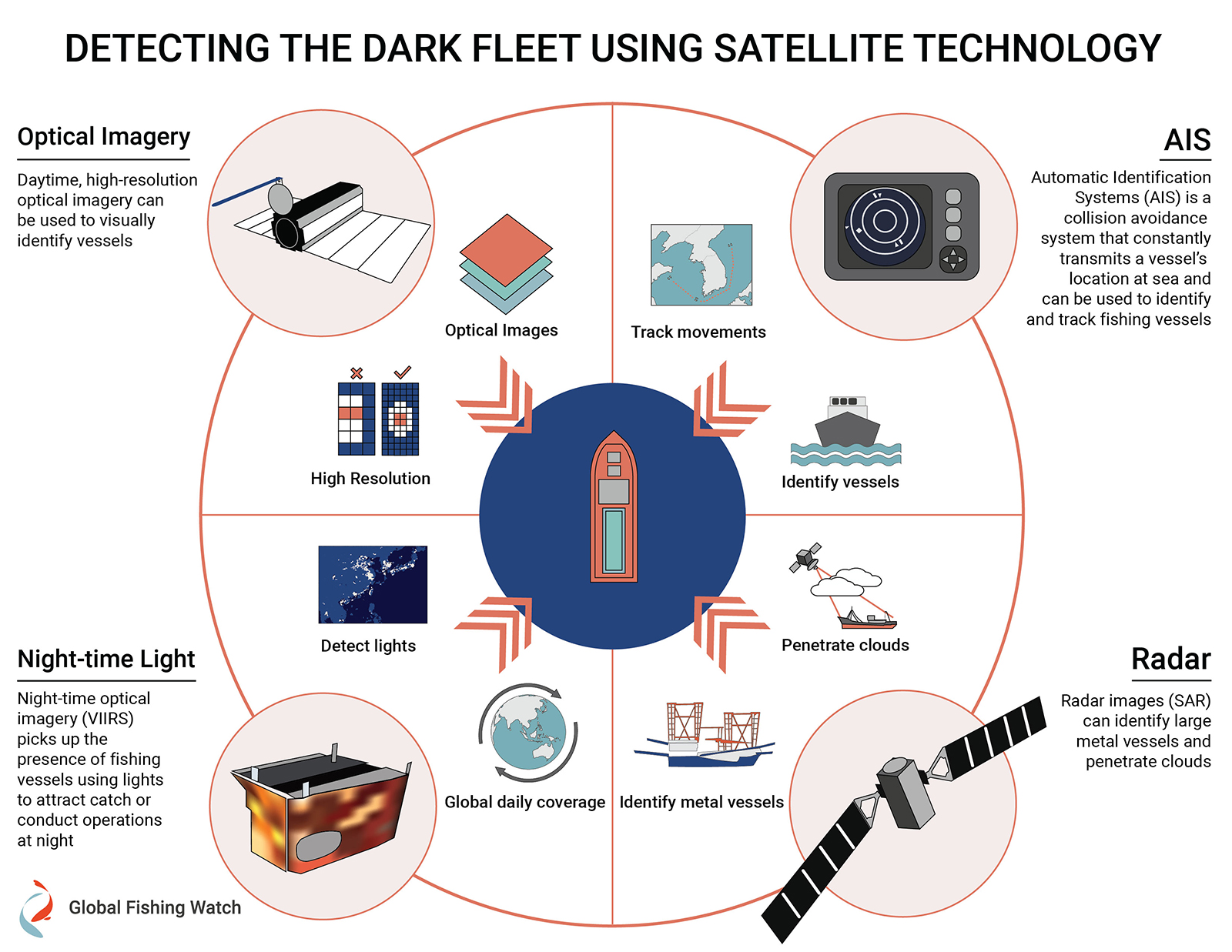

Fishing near the Ecuador, Peru and Argentina exclusive economic zones

Adapted from The New York Times. Note: “Other countries” are 35 entities including South Korea, Spain and Taiwan. Data is for the high seas within 50 nautical miles (about 57 miles) of the Ecuador, Peru and Argentina’s exclusive economic zones. Fishing activity near the disputed exclusive economic zone of the Falkland Islands was omitted. Data for 2022 is through May 31.

We know that the ocean is poised to become busier with an increasing level of human activity. Can you describe how the open ocean project will provide a more complete picture of these activities?

The open ocean project will focus on several categories of human activities: non-fishing vessels, industrial fishing and small-scale fishing (SSF) vessels, and fixed infrastructure. We have never been able to visualize SSF and fixed infrastructure at a global scale before, so this will have a revolutionary impact on our understanding of human activities at sea.

For infrastructure, we are aware that the ocean will have more pressures and conflicting uses. At a bare minimum, we need to understand what’s happening at baseline before we can make informed management decisions going forward. If we can’t see it, we can’t effectively manage it. The more we know about current uses, the more we can identify projects with co-benefits. One example is exploring whether we can site offshore wind turbines in a way that helps increase fish stocks, given that some emerging research suggests that turbine platforms may serve as artificial reefs.

Overall we’ve had such an information and data gap on human uses of the ocean. On the terrestrial side, we have detailed mapping of human activities—including roads, buildings, deforestation, and more. It’s exciting to see such great momentum building on the marine side, too.

This shows that shining a light can change behavior without any one country necessarily spending a lot of money on enforcement—there’s high value in a deterrence effect when people know that fishing activity is being monitored.

Reflecting on your professional journey, how have the advancements in fisheries transparency tools impacted your work as a researcher?

The existence of Global Fishing Watch has changed the trajectory of my career. I was working at NOAA Fisheries [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] when the organization came online and started to change the game.

Previously, due to data confidentiality requirements, I could only work on the economics of fishing and ocean management at a place like NOAA or another government agency with its own data on its national fleet. But once Global Fishing Watch came online, anyone could research fisheries from anywhere in the world. It was also a gamechanger in the types of research that was possible, due to the availability of data for international fleets. This revolution in transparency has allowed me to move to an academic institution where I’m now able to ask a whole realm of questions that I never dreamed of before.

Aside from the benefits to my own career and research, I especially appreciate that Global Fishing Watch has committed to a “forever free” model. Their guiding principle—that transparency is for the world; it’s not for sale—continues to advance the field in unprecedented ways.

The existence of Global Fishing Watch has changed the trajectory of my career. I was working at NOAA Fisheries when the organization came online and started to change the game. This revolution in transparency has allowed me to move to an academic institution where I’m now able to ask a whole realm of questions that I never dreamed of before.