Our Shared Seas interviewed two experts on the rapidly evolving field of global fisheries transparency. In the conversation below, Maisie Pigeon, Director of the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency describes a new initiative aimed at unifying organizations around the world in advancing best practices and policy outcomes for fisheries transparency. Tony Long, Chief Executive Officer of Global Fishing Watch also provides an update on the revolutions in ocean monitoring and analysis, including the organizations new open ocean project to map and monitor all human industrial activity at sea.

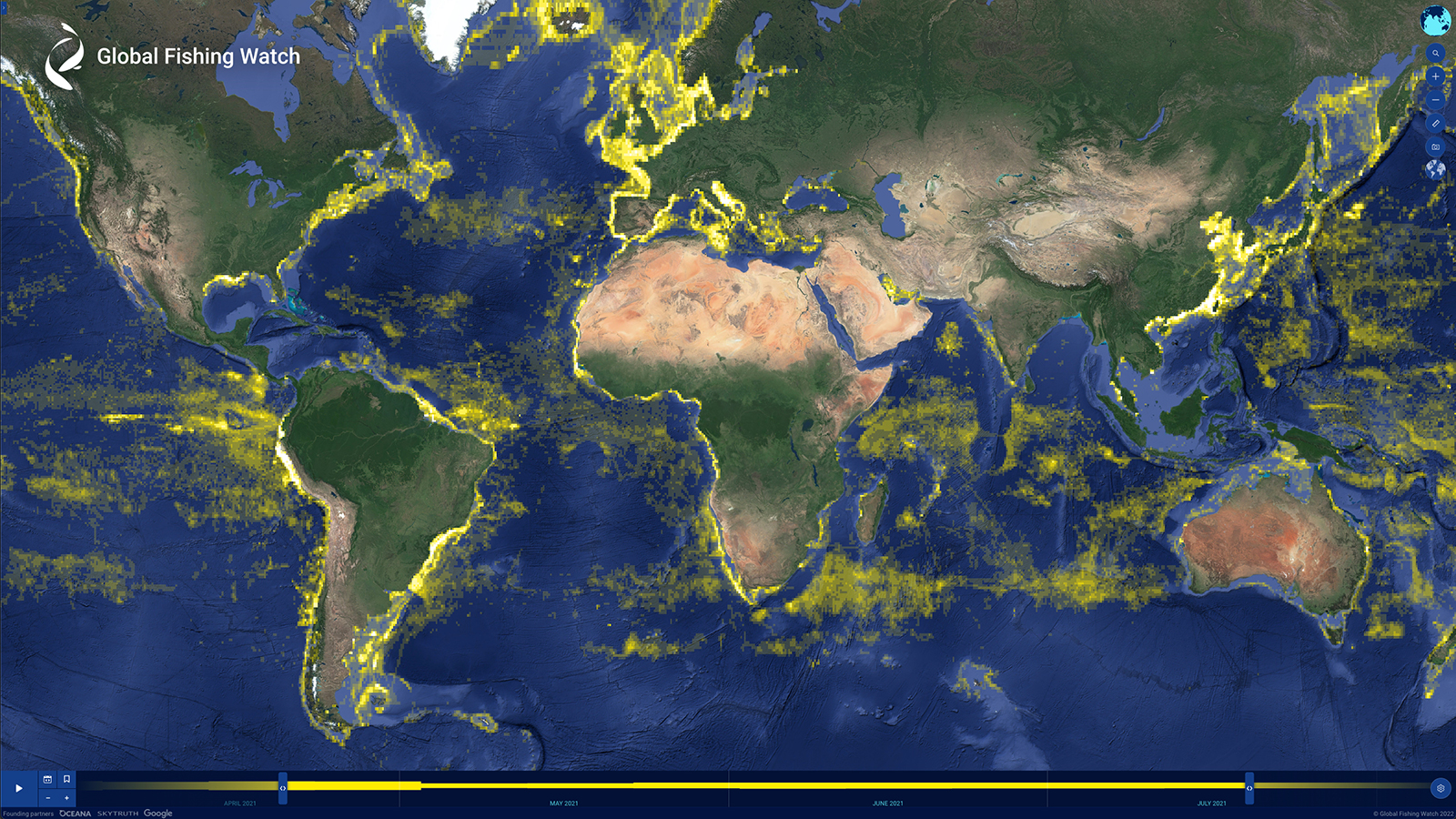

Global Fishing Watch seeks to advance increased transparency of human activity at sea. Through recent advances in satellite technology and machine learning, Global Fishing Watch has built an unprecedented open-access picture of global fishing activity. Photo: Global Fishing Watch

Can you provide an overview of the objectives of the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency?

Pigeon: The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency is a network of civil society organizations (CSOs) around the world that share a goal of policies which would improve transparency and accountability in fisheries. The Coalition—which currently has 35 members—is organized around a framework called the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency that outlines a set of ten policy priorities which are designed to be implemented by governments around the world.

Based on existing best practices in fisheries transparency, these principles address the lack of transparency in vessel information, fishing activity, and fisheries governance and management to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and over-fishing; prevent human rights and labor abuses at sea; support coastal communities; and promote good fisheries management, equitable participation in fisheries decision making, and sustainability. This framework launched in March 2023 alongside the Our Ocean Conference.

The Coalition for Fisheries Transparency is a network of civil society organizations around the world that share a goal of advancing policies which would improve transparency and accountability in fisheries. The Coalition is organized around a framework called the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency, designed to be implemented by governments.

What is the founding story for the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency?

Pigeon: The Coalition first started because there were well-documented instances of NGOs successfully pushing for fisheries transparency policy all over the world. But in many cases, these wins were pretty isolated, which limited the momentum to advance fisheries transparency on a broader scale. As a Coalition, we’re trying to connect these organizations to amplify our collective voice and coalesce around shared goals for fisheries transparency. In this way, the Coalition acts as a connective tissue between CSOs and provides a community of practice where organizations can share lessons learned and best practices on fisheries transparency. Global Fishing Watch is a coalition member and also sits on the steering committee; their team provides valued insights on which transparency policies are most effective and efficient.

What do you see as a growth area for the fisheries transparency movement?

Pigeon: Fisheries transparency is a cross-cutting issue that merits more attention. As an ocean conservation community, we have an untapped opportunity to partner with new stakeholders in this work—including those from the human rights, development assistance, and maritime security sectors. There is a vast audience of potential partners with shared interests—many with deep technical expertise—and we have a huge opportunity to collaborate on this work and maximize our collective outcomes.

Fisheries transparency is a cross-cutting issue that merits more attention. As an ocean conservation community, we have an untapped opportunity to partner with new stakeholders in this work – including those from the human rights, development assistance, and maritime security sectors.

Fish market in Tanzania. Photo: iStock / Sohadiszno

Global Fishing Watch recently received a $60 million investment through The Audacious Project. Can you share what this award will help the organization accomplish?

Long: The Audacious Project, which is housed at TED, is a collaborative funding initiative that invests in ambitious social impact ideas. Each year, they identify and bring forward a group of bold solutions to tackle the world’s most urgent challenges—and this year, they selected Global Fishing Watch.

Thanks to this investment, Global Fishing Watch will be able to build a “digital ocean” that reveals all industrial human activity at sea. Called the open ocean project, we will seek to build a comprehensive picture of what’s being done across the ocean, where and by whom. Processing millions of gigabytes of satellite data, we’ll map and monitor all industrial human activity at sea—including all industrial fishing vessels, hundreds of thousands of small-scale fishing boats, and all large non-fishing vessels like cargo ships, cruise liners, and oil tankers. The project will also reveal all oil and gas rigs, mining, and other fixed infrastructure like aquaculture pens and wind farms. By making the invisible visible, we’ll bring the ocean into focus for the first time—and this knowledge will be freely available for anyone to access and use.

Processing millions of gigabytes of satellite data, we’ll map and monitor all industrial human activity at sea—including all industrial fishing vessels, hundreds of thousands of small-scale fishing boats, and all large non-fishing vessels like cargo ships, cruise liners, and oil tankers.

Global Fishing Watch received a five-year USD $60 million commitment through The Audacious Project for its open ocean project. Over the next five years, the organization will publicly map more than one million ocean-going vessels and all fixed infrastructure at sea.

What does it look like to translate massive amounts of data and apply it in practice for monitoring or enforcement? Who are the end users, and what does your organization hope they will do with the data?

Long: Government agencies and decision makers make up a significant portion of our target audience as we strive to advance ocean governance. They rely heavily on technical experts who use our map to formulate data-driven insights which can help drive their respective policies forward. Our team’s recent work analyzing the jumbo squid fisheries in the Southeast Pacific Ocean is a great example of this. In 2020, as interest grew around vessel activity at the edge of the Galapagos Marine Reserve, Global Fishing Watch analysts used satellite radar and optical data to track the movements and behavior of the distant water squid fishing fleet. We found over 600 industrial-scale vessels—of which 95 percent came from China—fishing on the high seas to the west of South America. Our analysis brought several issues to light, including instances where vessels were either concealing their positions or broadcasting false ones. The data also identified a major discrepancy in transshipment, the practice of transferring catch between vessels, whereby the number of vessels engaged in the activity was different from what was actually being reported.

North Korean squid boats in operation in the Russian EEZ recorded between August and October 2018. All are wooden boats less than 20 meters long and bear the North Korean flag. They are generally equipped with only 5-20 light bulbs used to lure squid at night. They use driftnets during the daytime, and the squid catch is usually dried on the deck probably due to the lack of refrigeration systems. Photo: Seung-Ho Lee

We provided detailed reports to the governments of Ecuador, Chile, and Peru, and our team’s findings received widespread coverage in major international outlets. In 2021, the Chinese fleet kept its distance from the Galapagos for the first time in five years. This shows the impact of our work and how our data can be used in government outreach, in tandem with increasing public awareness, to result in change on the water.

At the same time, researchers around the world are also using Global Fishing Watch data for original research. Previously, you would have to go country-by-country to ask government agencies for their fishing data—this is a cumbersome process and would often result in incomplete data. Global Fishing Watch takes millions of gigabytes of information and combines it with satellite tracking and radar to shed light on what is happening at sea. We make this information freely available to the world—anyone is welcome to access and use this data. Our organization’s founding rested on the notion that if Global Fishing Watch made this data available, people would use it—and we knew research would be a primary application. It’s amazing to see this happening in practice as researchers advance ocean science.

We provided detailed reports to the governments of Ecuador, Chile, and Peru, and our team’s findings received widespread coverage in major international outlets. In 2021, the Chinese fleet kept its distance from the Galapagos for the first time in five years. This shows the impact of our work and how our data can be used in government outreach, in tandem with increasing public awareness, to result in change on the water.

The Global Fishing Watch map is the first open-access online tool for visualization and analysis of vessel-based human activity at sea. The map monitors global fishing activity from 2012 to the present for more than 65,000 commercial fishing vessels that are responsible for a significant part of global seafood catch. Image: Global Fishing Watch

What do you perceive as the specific role of governments in fisheries transparency work?

Long: When I started at Global Fishing Watch in 2017, the organization’s core product was ostensibly a map with a lot of research being done from it. My vision for the organization was to accelerate the change that the map could facilitate. We initiated a policy-based program to work with countries to share their vessel tracking information so that we could have a better understanding of what was happening out on the water.

The reality was that much more was needed than vessel tracking alone to protect the ocean and safeguard marine resources. In tandem, partners like the Environmental Justice Foundation and Oceana were also advocating for fisheries transparency. But we were all effectively working in our own lane. We knew that by coming together, we could maximize our collective efforts. At this point, Oceans 5 and Bloomberg Philanthropies helped bring together the Coalition for Fisheries Transparency, which established a framework of best practices on what governments should do to address the lack of transparency in fishing activity, vessel information, and fisheries governance and management to combat illegal fishing and prevent human rights abuses at sea.

Ultimately governments are responsible for what happens on the ocean and for taking appropriate action in its management and enforcement. Once that starts to happen, a more virtuous cycle falls into place—one where the public applies external pressure and begins to demand a clearer understanding of where and how their seafood has been sourced. At Global Fishing Watch, we are putting our data and tools in the hands of governments so that they can take action to enable fair and sustainable use of our global ocean.

Global fisheries transparency is now possible given recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning. What we have now—an open-access, freely available dataset on global fishing activity—is a vast improvement to the darkness we were operating in just a decade ago.

What are some of the key factors that have resulted in recent advancements in the fisheries transparency space?

Long: A few years ago, monitoring the whole of the ocean was something most people did not believe was possible—the activities that take place beyond the horizon are often seen as “out of sight, out of mind.”

Global fisheries transparency is now possible given recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning. What we have now—an open-access, freely available dataset on global fishing activity—is a vast improvement to the darkness we were operating in just a decade ago.

With these new tools, we are starting to see several positive forces coming together at the right time. Governments and other stakeholders have realized that fisheries transparency and open data can be used jointly to monitor what is happening out on our ocean and drive good governance. I’m optimistic that partners are stepping up and everyone is pulling in the right direction to safeguard our global ocean for the common good of all.

Governments and other stakeholders have realized that fisheries transparency and open data can be used jointly to monitor what is happening out on our ocean and drive good governance. I’m optimistic that partners are stepping up and everyone is pulling in the right direction to safeguard our global ocean for the common good of all.