From December 7-19, Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) will meet for the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to determine the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. After two years of delays due to the Covid-19 pandemic, many are looking to COP15 as an opportunity to set an ambitious path forward in safeguarding nature for the health of people and the planet. Brian O’Donnell, Director of the Campaign for Nature shared a detailed update on the current state of play and priorities for the conservation community after the COP15 meeting concludes.

Coral reefs support the highest biodiversity of any ecosystem globally and directly support at least 500 million people worldwide, especially in poor countries. Particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, coral reefs are emblematic of the interlinked biodiversity-climate crises. The future of coral reefs and the biodiversity that they support are contingent on addressing the drivers of climate change. Photo: Renata Romeo / Ocean Image Bank

Can you set the scene on the status of the draft global biodiversity framework in the lead up to the COP15 meeting next week?

Here we are a few years delayed from when COP15 was originally set to take place. The COP15 meeting has been moved to Montreal, from the original meeting place of Kunming, China. To date, there have been four formal negotiating sessions as well as several online negotiating sessions. To be honest, these sessions have made very little progress. The first negotiating session started with a draft from the Open-ended Working Group. The two co-chairs put together a draft post-2020 global biodiversity framework, which included at the time about 20 targets organized to help address the biodiversity crisis. Several of these targets are critically important for the ocean, including targets around:

- How much area of the ocean we should protect and conserve by 2030. The draft target currently calls for protecting 30 percent of the ocean by 2030.

- Pollution issues, including a proposal to eliminate plastic pollution

- Subsidies reform, including eliminating harmful capacity-enhancing subsidies that incentivize overfishing

These negotiating sessions were generally attended by the focal points to the CBD—which often includes staff within environment ministries. We’ve not seen high-level political engagement; the process has taken place at a technical level. Partly as a result, we’ve seen concise, easy-to-communicate targets that were previously one sentence balloon into several paragraphs of text that can be difficult to follow. The target text tends to grow and grow, as some negotiators prefer different—and occasionally contradictory—language. Because of this process, negotiators may not ultimately agree to the emerging text. We now find ourselves with text that has swelled: most of it remains in square brackets, meaning that it is not yet formally agreed to. Most negotiators would say that this is the normal process—that the framework is on a rollercoaster path, right up until the end of the meeting when agreements are finalized. That said, there was originally the perception that 80 percent of the text would be agreed to prior to COP15. In reality, this ratio is flipped: negotiators have agreed to only about 20 percent of the text. This leaves a tremendous amount of work to accomplish at COP15.

The other challenge is the anticipated lack of high-level political engagement at the COP15 meeting. At COP27—the UN Climate Summit that took place last month—there were over 90 heads of state who actively participated and more than one hundred environment ministers who stayed at the meeting for at least two weeks. In contrast, no heads of state have been invited to join COP15, and environment ministers are only scheduled to be at the meeting for about two days. This means that high-level political engagement will be limited to only a few hours at COP15. This is a tremendous amount of pressure to agree upon a framework of this significance in a compressed timeframe. While it doesn’t mean that securing a global framework for biodiversity is impossible, it does imply that the stakes are high and the window of opportunity is limited.

WG2020-4 Contact Groups, 22 June 2022. Photo: Convention on Biodiversity via Flickr

High-level political engagement will be limited to only a few hours at COP15. This is a tremendous amount of pressure to agree upon a framework of this significance in a compressed timeframe. While it doesn’t mean that securing a global framework for biodiversity is impossible, it does imply that the stakes are high and the window of opportunity is limited.

What are some of the most pressing issues going into COP15?

Funding remains the biggest issue, including how much funding will be available to implement an ambitious global biodiversity framework. Most of the world’s remaining biodiversity tends to be concentrated in developing nations and their territories and waters. In these places, there will be an outsized effort to help conserve biodiversity over the next decade. Rightfully, these countries and communities are asking what level of support will be available from wealthy nations, the philanthropic sector, and the business community. To date, the level of support has been thin.

We do expect to see an increase in finance. Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Canada, and others have announced an increase in biodiversity finance. This is a promising sign at a time when overall official development assistance levels have been declining. Still, biodiversity finance is not increasing nearly fast enough commensurate with the scale of the opportunity and the necessity for an ambitious framework.

The Campaign for Nature has called for about USD 60 billion per year of public finance from wealthy nations to developing nations, as well as direct access to those funds for Indigenous peoples (IPs) and local communities (LCs) to address biodiversity loss. We do not expect that wealthy nations will be putting funding anywhere close to this level on the table next week in Montreal. The question is to what extent can we increase public funding levels over the remainder of this decade, given that the global biodiversity framework will last from 2022 to 2030. Many wealthy countries are talking about fiscal challenges that they’re currently facing, from inflation and budget constraints to energy prices and the war in Ukraine. We have to think that these conditions will evolve in future years and that country budgets may be in better financial shape, with room to increase biodiversity funding.

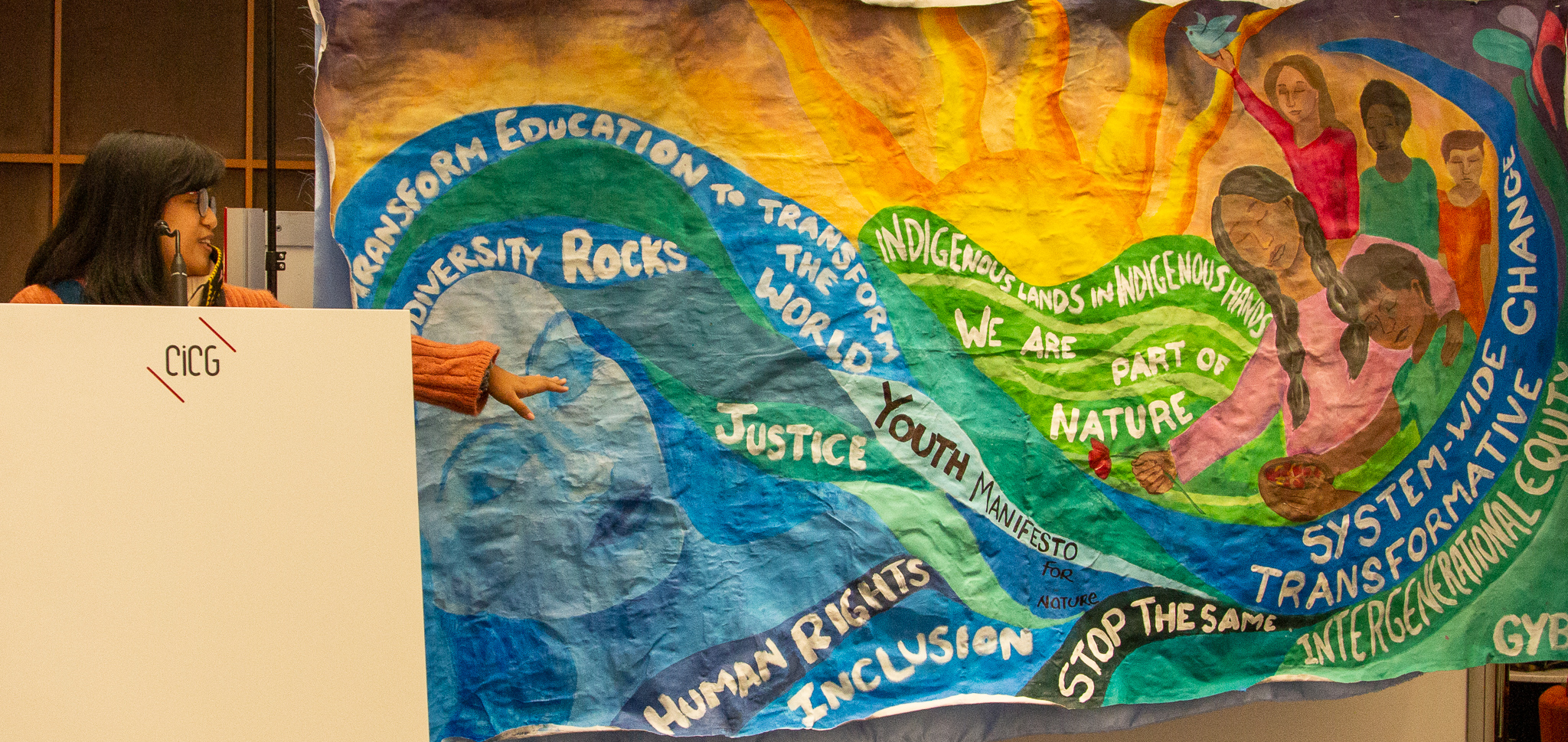

Side event hosted by Global Youth Biodiversity Network, during which a mural was unveiled. Photo: Convention on Biological Diversity via Flickr

Beyond funding, another key issue at COP15 will be the extent to which the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities are recognized. We have seen strong rhetoric in favor of recognizing these rights, in addition to general agreement from negotiators. Now we need to see the recognition of rights fully articulated in the draft targets and the overall framework; this is an essential component to COP15.

Another issue at play in COP15 is the overall ambition of the framework. Will the framework seek to halt and reverse biodiversity loss in an ambitious way? Many organizations are calling for the framework to have a nature-positive mission, rather than simply aiming to slow down biodiversity decline. This will be a key question that negotiators and delegates discuss.

Finally, there is a question of how many targets can negotiators focus on? As early as today, China has called for an “ambitious but practical” deal. It is sometimes hard to square this circle: “practical” sounds like business as usual, which has led us to today’s biodiversity crisis. I am strongly in favor of pushing for ambitious targets at COP15, rather than lowering expectations before day one of the meeting. Although China did rightfully note the failure of the global community to meet many of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets in 2020, there is opportunity to learn from these lessons—including ensuring adequate finance, inclusive participation of Indigenous peoples and local communities, and political buy-in from governments.

Beyond funding, another key issue at COP15 will be the extent to which the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities are recognized. We have seen strong rhetoric in favor of recognizing these rights, in addition to general agreement from negotiators. Now we need to see the recognition of rights fully articulated in the draft targets and the overall framework; this is an essential component to COP15.

Can you share more insights into if and how the CBD negotiations process is recognizing the rights and priorities of Indigenous peoples and local communities?

From a general standpoint, the CBD can be disenfranchising to Indigenous peoples. By definition, members of the Convention are States. Indigenous peoples are not recognized as States by the Convention, so they are treated as formal observers rather than negotiators with formal authority to vote or block. This is a structural challenge in the UN system—for climate negotiations, biodiversity negotiations, and other processes.

WG2020-4 – Opening Plenary – 21 June. Photo: Convention on Biological Diversity via Flickr

Within the current construct, there is the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity (IIFB), which is a coalition of Indigenous organizations that work to speak with one voice in the negotiations. The IIFB becomes the main voice of Indigenous peoples and local communities in the negotiations themselves. To date, we have seen the IIFB play a very active role in recommending new targets, alternate language, and adjustments to the targets. There has also been some effort to place the rights of Indigenous peoples in the preamble of the whole framework, under the notion that the framework should be adopted in a rights-based way. This is a positive sign, but the challenge is that many implementers of the framework tend to pull out the targets one-by-one. For this reason, it is useful to have redundancies to ensure that rights-based language is incorporated throughout the framework, which is a case that the IIFB has been making.

We have seen many of the IIFB’s recommendations incorporated into the latest draft, which is encouraging. The IIFB has also been working with the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, which is an intergovernmental group of more than 115 countries that have endorsed the target to protect 30 percent of land and water by 2030. Both the IIFB and the High Ambition Coalition meet regularly and work to align on the target language. This has been a successful endeavor and a notable change from recent COP meetings. It comes from a recognition that in order for the global biodiversity framework to be successful, it must include a rights-based approach for Indigenous peoples as well as their support for the framework. I am optimistic that this will be one of the bright spots of the framework.

Looking forward, a key issue is if and how funding will reach Indigenous peoples who are implementing the global biodiversity framework. Most funding goes through big multilateral institutions such as the Global Environment Facility, World Bank, and international development banks. These agencies often do not fund Indigenous peoples, or if they do, it’s difficult for IPs to access the funding. This is an area where philanthropy can play an important role in finding ways to efficiently direct funding to Indigenous peoples and local communities. Marine funders have an opportunity to look closely at their grantmaking and examine how much is truly meeting the frontline defenders of biodiversity.

This is an area where philanthropy can play an important role in finding ways to efficiently direct funding to Indigenous peoples and local communities. Marine funders have an opportunity to look closely at their grantmaking and examine how much is truly meeting the frontline defenders of biodiversity.

What trends are you seeing in terms of philanthropic funding for Indigenous peoples and organizations in the marine versus terrestrial space?

Conservation funding for Indigenous peoples started in the climate space, which historically prioritized forest communities above pastoralists. Ocean communities are much further behind even pastoralists in receiving funding from philanthropy—this is due, at least partly, to the global community’s lack of appreciation for the ocean’s importance from a climate and biodiversity standpoint.

When you look at Indigenous peoples’ organizations at the COP, they tend to be from the terrestrial space, and we see less representation from ocean and coastal communities. This is an “out of sight, out of mind” challenge in that we see lower participation at the COP from marine-oriented Indigenous organizations. Still, funders need to recognize that coastal Indigenous communities are critically important to the effective implementation of the global biodiversity framework.

Fishing in Godavari mangrove forest. Photo: Srikanth Mannepuri / Ocean Image Bank

Historically, finance and resource mobilization have been under-recognized pieces of the puzzle for the global biodiversity framework. What is the status of the funding component, particularly given the challenging economic circumstances that many countries face today?

There is still a huge delta in both trust and money between developing countries and wealthy countries. If you look at the recent UN Climate Summit, it is telling about what we may face at COP15. Since the Paris Agreement in 2015, there was a commitment for USD 100 billion to support developing countries in implementing climate policies. This funding has not yet materialized from wealthy nations, and it has left a legitimate sense of betrayal and mistrust from developing nations.

At COP27 a few weeks ago, a new fund for “loss and damage” was developed to assist developing countries hit hard by climate disasters. This represented an increased recognition of wealthy nations’ responsibility to address their climate impacts. The caveat is that this new fund included a structure but not the actual funding for loss and damage. We face a similar context going into COP15: developing nations are calling for a new fund to finance biodiversity, which would be outside of existing funds and not double counted through climate commitments. Countries have called for different levels of support, but one of the most recent calls was for USD 100 billion per year of new funding for biodiversity protection. The Campaign for Nature and collaborators recently completed a deep dive to track how much money is supporting biodiversity from governments, philanthropy, and corporations. We are seeing about USD 6.2 billion per year for biodiversity; this is a long way from the call for a USD 100 billion fund.

Photo: Matt Curnock / Ocean Image Bank

There are several bright spots in the finance dialogue. One development is debt restructuring, which we have recently seen in Belize and the Seychelles. Given the state of the world’s economic situation, many countries are close to defaulting on foreign debts; this could be an opportunity to relieve that pressure while also garnering support for nature conservation and climate action. This is a potential new approach, though it is just getting off the ground, so it may be part of the conversation even if the mechanics may not be ready for COP15.

We are also seeing some changes from multilateral development banks to align their projects as “biodiversity positive.” There are also biodiversity pledges from corporations, which tend to be a positive sign but should be regarded with a healthy dose of caution given that they are voluntary.

If governments are serious about finding funding for ocean and terrestrial conservation, one opportunity is to look to the windfall of the oil and gas industry. Even in the last quarter alone, there are billions of dollars in windfall profits that could be allocated to biodiversity funding.

COP15 will occur on the heels of the COP27 meeting. In what ways are there similarities and differences between the biodiversity negotiations and climate negotiations processes?

If we could go back in time to the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, we would have benefitted from not creating two separate conventions on biodiversity and climate. This has contributed to governments’ inability to give full-fledged attention to both the biodiversity crisis and climate crisis in an integrated way. Governments have consequently given more attention to climate and have relegated biodiversity to a lower-tier priority. This treatment is not viable to the future of all life on Earth; we need to address both biodiversity and climate in a holistic manner.

At COP27, there was an attempt to call for a strong implementation of a post-2020 biodiversity framework. Much of the climate mitigation and sequestration solution is in protecting nature, and this was acknowledged throughout the COP27 process. However, some parties contended that we must keep the climate process and biodiversity process separate, maintaining antiquated walls between the two conventions. This loses opportunities for synergies. Also, there were 90 heads of state that attended the climate summit, and none are expected to attend the biodiversity summit.

We won’t solve the climate crisis without protecting the ocean, forests, peatlands, and mangroves. And we won’t solve the biodiversity crisis unless we address climate change and radically reduce emissions. We need to address both climate change and biodiversity decline in concert to win either of these issues. They are both critical to the viability of humanity and all other species on the planet.

Spearfisher in Alor, Indonesia. Photo: Erik Lukas / Ocean Image Bank

In recent years, we have seen increased recognition of the importance of biodiversity, but structurally within the UN system, biodiversity is still behind climate. Despite some improvements—like the spotlight on the ocean at the “Blue COP” in 2019—there are still barriers between the two COPs. On the funding side, substantially more funding from public and private sources goes into climate as compared to biodiversity. We can’t have an ambitious biodiversity framework unless we start to see funding on the same scale as climate.

Stepping back, there is a recognition that we may need to revisit both conventions. When you look at the outcomes, neither the climate nor the biodiversity convention has been particularly successful. While climate has received more political attention, emissions continue to rise. Biodiversity is declining at rates unprecedented in human history. So while both conventions have raised the visibility of these issues and achieved important actions, neither is succeeding yet. There is almost an industrial complex at the conventions that the issue can be addressed in incremental ways year after year. The science shows we need transformational action right now. I think COP15 has a real chance to shine and achieve an ambitious framework, but we have our work cut out for ourselves.

We won’t solve the climate crisis without protecting the ocean, forests, peatlands, and mangroves. And we won’t solve the biodiversity crisis unless we address climate change and radically reduce emissions. We need to address both in concert to win either of these issues. They are both critical to the viability of humanity and all other species on the planet.

As we look beyond the COP15 meeting itself, what are priorities to ensure a successful and equitable implementation of the global biodiversity framework?

Implementation is the most important part of the global biodiversity framework. Targets without implementation are simply high-profile failures. What’s different this time, as compared to the Aichi Targets, is that people are beginning to recognize that parties need support in developing their National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAP). For instance, Columbia has prepared a NBSAP Accelerator, with some additional funding from Germany that will help countries develop these plans. This means that countries will be able to access resources off the bat for planning. Public and private donors usually require these plans as a pre-requisite for funding to ensure that the biodiversity strategies are transparent, inclusive, and equitable.

In 2023, we also expect to see biodiversity finance plans to support implementation of the biodiversity framework. This is a positive sign to see an articulation of where the resources will come from. Philanthropy already has new ambitious approaches for biodiversity protection. One example is Enduring Earth, which mobilizes long-term funding for protected areas. Another example is the Legacy Landscapes which seeks to fund a diverse portfolio within the world’s most relevant biodiversity hotspots by 2030. The Global Environment Facility has talked about accelerating its processes and getting funding out the door faster. There are also emerging mechanisms to fund Indigenous peoples and local communities more directly; one example is CLARIFI to provide funding to frontline forest defenders. We are also seeing some increases in support from public funding sources, including the United States. With the recent election in Brazil, their government has switched from being a blocker to an enthusiastic supporter of biodiversity protection. Lastly, there is increased alignment emerging between biodiversity and conservation finance. These are all encouraging signs.

Implementation is the most important part of the global biodiversity framework. Targets without implementation are simply high-profile failures.

Looking forward, how can the conservation community best support this work? What are the unique roles that philanthropy and NGOs can play in advancing equitable implementation of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework?

Because we have been talking about a global framework, we see offices in capital cities or the UN hubs receiving a large share of recent biodiversity funding. As we start to transition to implementation, we need to resource people on the frontlines doing this work on the ground and on the water. NGOs and philanthropies need to retool where their money is going and who they are supporting. We cannot maintain the same structure to negotiate an agreement as to implement one; there is an opportunity to evolve this approach. A significant portion of funding should go to Indigenous peoples and local communities, and we need to support effective structures to facilitate this transfer.

Among NGOs and philanthropic engagement on this issue, there is one striking area that has been missing from the conversation. Governments currently spend a miniscule amount on nature conservation, which is astonishing given that our climate stability, livelihoods, food, and public health depend on thriving natural systems. Civil society works closely on policy advocacy for protected areas, but there is very little engagement on the public finance side. We do not see many NGO employees or an adequate level of philanthropic funding to advocate for increased public funding for biodiversity. Insufficient funding is one of the main reasons that biodiversity projects and strategies hit roadblocks and become unsuccessful. This is an untapped opportunity for both NGOs and philanthropy to pay more attention to public finance so that we can see a noticeable increase in biodiversity funding moving forward.

Coral reef, French Polynesia. Photo: Hannes Klostermann / Ocean Image Bank

Governments currently spend a miniscule amount on nature conservation. This is an untapped opportunity for both NGOs and philanthropy to pay more attention to public finance so that we can see a noticeable increase in biodiversity funding moving forward.